UPDATED July 25, 2022 // Editor's note: This story has been updated with additional comments from Dr Maria Carrillo of the Alzheimer's Association.

A US neuroscientist claims that some of the studies of the experimental agent, simufilam (Cassava Sciences), a drug that targets amyloid beta (Aβ) in Alzheimer's disease (AD), are flawed, and, as a result, has taken his concerns to the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Matthew Schrag, MD, PhD, department of neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, uncovered what he calls inconsistencies in major studies examining the drug.

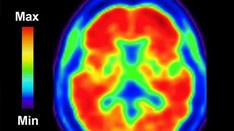

In a whistleblower report to the NIH about the drug, Schrag claims that several prominent investigators altered images and reused them over years to support the hypothesis that buildup of amyloid in the brain causes AD. The NIH has funded research into Aβ as a potential cause of AD to the tune of millions of dollars for years.

"This hypothesis has been the central dominant thinking of the field," Schrag told Medscape Medical News. "A lot of the therapies that have been developed and tested clinically over the last decade focused on the amyloid hypothesis in one formulation or another. So, it's an important component of the way we think about Alzheimer's disease," he added.

In an in-depth article published in Science on July 22 and written by investigative reporter Charles Piller, Schrag said he became involved after a colleague suggested he work with an attorney investigating simufilam. The lawyer paid Schrag $18,000 to investigate the research behind the agent. Cassava Sciences denies any misconduct, according to the article.

Schrag ran many AD studies through sophisticated imaging software. The effort revealed multiple Western blot images — which scientists use to detect the presence and amount of proteins in a sample — that appeared to be altered.

High Stakes

Schrag found "apparently altered or duplicated images in dozens of journal articles," the Science article states.

"A lot is at stake in terms of getting this right and it's also important to acknowledge the limitations of what we can do. We were working with what's published, what's publicly available, and I think that it raises quite a lot of red flags, but we've also not reviewed the original material because it's simply not available to us," Schrag told Medscape Medical News.

However, he added that despite these limitations he believes "there's enough here that it's important for regulatory bodies to take a closer look at it to make sure that the data is right."

Science reports that it launched its own independent review, asking several neuroscience experts to also review the research. They agreed with Schrag's overall conclusions that something was amiss.

Many of the studies questioned in the whistleblower report involve Sylvain Lesné, PhD, who runs The Lesné Laboratory at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and is an associate professor of neuroscience. His colleague Karen Ashe, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology at the same institution, was also mentioned in the whistleblower report. She was coauthor of a 2006 report in Nature that identified an Aβ subtype as a potential culprit behind AD.

Medscape Medical News reached out to Lesné and Ashe for comment, but has not received a response.

However, an email from a University of Minnesota spokesperson said the institution is "aware that questions have arisen regarding certain images used in peer-reviewed research publications authored by University faculty Karen Ashe and Sylvain Lesné. The University will follow its processes to review the questions any claims have raised. At this time, we have no further information to provide."

Asked to comment, Maria Carrillo, PhD, chief science officer of the Alzhiemer's Association, told Medscape Medical News that if the "accusations of falsification of images or data are true, there needs to be appropriate accountability for all responsible — including the scientists, their facility, the journals, and funders."

Accountability would include admission of falsification, retraction of falsified images or data, return of funds and ineligibility of future funding for those found responsible, and new or stronger enforcement of policies to prevent repetition of these false actions, she added.

A Matter of Trust

Schrag noted the "important trust relationship between patients, physicians and scientists. When we're exploring diseases that we don't have good treatments for." He added that when patients agree to participate in trials and accept the associated risks, "we owe them a very high degree of integrity regarding the foundational data."

Carrillo agreed. "There is great urgency for advances in diagnosing, reducing risk, treating and preventing Alzheimer’s disease and all dementia, but there is no room for shortcuts based on dishonesty and deception," she said. "We owe that to all those who have been impacted by Alzheimer’s, people living with Alzheimer's, their families, people at risk, research participants and the medical and research community."

Schrag also pointed out that there are limited resources to study these diseases. "There is some potential for that to be misdirected. It's important for us to pay attention to data integrity issues, to make sure that we're investing in the right places."

The term "fraud" does not appear in Schrag's whistleblower report, nor does he claim misconduct in the report. However, his work has spurred some independent, ongoing investigation into the claims by several journals that published the works in question, including Nature and Science Signaling.

Schrag said that if his findings are validated through an investigation he would like to see the scientific record corrected.

"Ultimately, I'd like to see a new set of hypotheses given a chance to look at this disease from a new perspective," he added.

"As we continue to move forward, it is important to note that this investigation is related only to a small segment of Alzheimer's and dementia research and does not reflect the full body or science in the field," Carrillo said.

Potential treatments that address the full scope of Alzheimer's biology are advancing, she added. "Future treatments will need to address amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration as well as other brain changes that play a role in the disease."

Schrag notes that the work described in the Science article was performed outside of his employment with Vanderbilt University Medical Center and that his opinions do not necessarily represent the views of Vanderbilt University or Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Science. Published online July 21, 2022. Full text

Damian McNamara is a staff journalist based in Miami. He covers a wide range of medical specialties, including infectious diseases, gastroenterology, and critical care. Follow Damian on Twitter: @MedReporter.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and LinkedIn.

Credits:

Lead image: Skypixel/Dreamstime

Medscape Medical News © 2022

Cite this: Neuroscientist Alleges Irregularities in Alzheimer's Research - Medscape - Jul 22, 2022.

Comments