Advertisement

Your inhaler saves lives, but its puffs hurt the planet

Resume

Dr. Miguel Divo, a lung specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, sits in an exam room, across from one of his patients with asthma. Joel Rubinstein, a retired psychiatrist, is about to get a check-up and to hear a surprising pitch — for the planet.

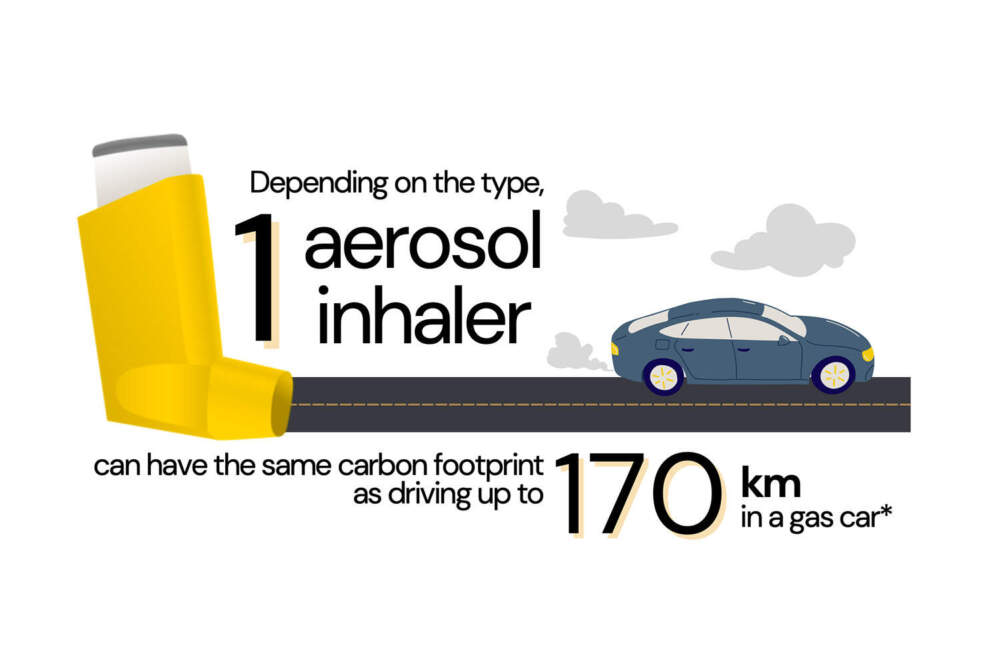

Divo starts with the dilemma. The little boot-shaped inhalers that represent nearly 90% of the U.S. market save lives. But they’re also helping warm the earth: Each puff from the inhaler releases a hydrofluorocarbon gas that is 1,430 to 3,000 times more powerful than the most commonly known greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide.

“That absolutely never occurred to me,” said Rubinstein. “Especially, I mean, these are little teeny things.”

So Divo has begun offering a more climate-friendly option to some patients with asthma and other lung diseases. He holds up a hard plastic gray cylinder, about the size of a hockey puck that contains powdered medicine. Patients suck the powder into their lungs — no puff of gas required — no greenhouse gas emissions.

“You have the same medications,” Divo says, “two different delivery systems.”

Moving away from puffers could add up. Patients are prescribed roughly 144 million of what doctors call metered-dose inhalers a year. The cumulative amount of gas released is the equivalent of driving half a million gas powered cars for a year.

The gas contributes to global warming, which is linked to more fires, smoke, other types of air pollution and longer allergy seasons. These conditions can make breathing more difficult — especially for people with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) — and increase their use of inhalers.

Divo is one of a small but growing group of U.S. physicians determined to reverse what they see as a vicious, unhealthy cycle.

“There is only one planet and one human race,” Divo says. “We are creating our own problems … and we need to do something.”

So Divo is working with patients like Rubinstein who may be willing to switch to dry powder inhalers. Rubinstein said no initially because the dry powder inhaler would have been much more expensive. Then his insurer increased the co-pay on the metered-dose inhaler, and Rubinstein decided to give the dry powder option a try.

“For me, price is a big thing,” said Rubinstein, who has tracked health care and pharmaceutical spending for years. And inhaling the medicine using his own lung power was an adjustment: “The powder is a very strange thing, to blow powder into your mouth and lungs.”

But for Rubinstein, the new inhaler works. His asthma is under control. Patients in the United Kingdom who use these inhalers have better asthma control while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In Sweden, where the vast majority of patients use dry powder inhalers, rates of severe asthma are lower than in the U.S.

Rubenstein is one of a small number of U.S. patients who have made the transition. Only about 25% of Divo’s patients even consider switching. For many, dry powder inhalers are more expensive. Not all asthma or COPD patients can get their meds in this form. And the dry powder method isn’t generally recommended for young children or elderly patients with diminished lung strength.

Some patients worry more when they use dry powder, because without the noise from the spray, they aren’t certain they are getting their medicine. Others don’t like the different taste powder inhalers can leave in their mouths.

Divo says making sure patients have an inhaler they are comfortable using and can afford is his priority. But when appropriate, he’ll keep raising the dry powder option.

Asthma and COPD patient advocacy groups also support more conversations about the connection between inhalers and climate change.

“The climate crisis makes these individuals have a higher risk of exacerbation and worsening their disease,” said Dr. Albert Rizzo, chief medical officer at the American Lung Association. “We don’t want the medications they're using to contribute to that.”

Rizzo says there are changes in the works for metered-dose inhalers that could one day make them more climate-friendly. The U.S. and many other countries are phasing down use of hydrofluorocarbons, the gasses in metered-dose inhalers as well as refrigerators and air conditioners. But inhaler manufacturers are largely exempt from those requirements, and can continue using them while they explore new options.

Some leading inhaler manufacturers have pledged to produce canisters with less potent greenhouse gasses and submit them for regulatory review by next year. It’s not clear when these inhalers might be available in pharmacies. Separately, the Food and Drug Administration is spending $6 million on a study about the challenges of developing inhalers with lower global warming impact.

Rizzo and other lung specialists worry these changes will translate to price hikes. That’s what happened in the early to mid 2000s when ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were phased out. Manufacturers changed the gas in metered-dose inhalers, and the cost to patients nearly doubled. Today, many of those inhalers remain expensive.

Dr. William Feldman says these dramatic price increases occur because manufacturers register updated inhalers as new products even though they deliver medications already on the market. Then they’re awarded patents, which prevent the production of competing generic medications for decades.

After the CFC ban, “manufacturers earned billions of dollars from the [revised] inhalers,” says Feldman.

When inhaler costs went up, physicians say patients cut back on puffs and suffered more asthma attacks. Dr. Gregg Furie, medical director for climate and sustainability at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, is worried that’s about to happen again.

“While these new propellants are potentially a real positive development,” said Furie, “there’s also a significant risk that we’re going to see patients and payers face significant cost hikes.”

Some of the largest inhaler manufacturers are already under scrutiny for allegedly inflating prices in the U.S. A spokesperson for GSK says the company has a strong record for keeping medicines accessible to patients but that it’s too early to comment on the price of inhalers the company is developing to reduce global warming.

Seeking affordable, effective and climate-friendly inhalers amid all these possible changes will be important for some hospitals as well as patients. Reducing inhaler emissions is a recommended priority for hospitals working to lower their carbon footprint. Some see switching inhalers as “low-hanging fruit” on the list of climate change improvements a hospital might make. But other experts disagree.

“It’s not as easy as swapping inhalers,” said Dr. Brian Chesebro, medical director of environmental stewardship at Providence, a hospital network in Oregon.

Chesebro says pharmacists who fill inhaler prescriptions could suggest inhalers with fewer greenhouse gas emissions — even among metered-dose inhalers, the climate impact varies. Insurers could adjust reimbursements to favor climate-friendly alternatives. Regulators could consider emissions when reviewing hospital performance.

Dr. Samantha Green, a family physician in Toronto, says clinicians can make a big difference with inhaler emissions by starting with this question: Does the patient in front of me really need one?

Green, who works on a Canadian sustainability project, says research shows about 30% of patients who report having asthma don’t have the disease.

“So that’s an easy place to start,” Green said. “Make sure the patient prescribed an inhaler is actually benefiting from it.”

And Green says educating patients has a real and measurable impact. In her experience, patients are moved to learn that emissions from one inhaler are equivalent to driving about 100 miles in a gas-powered car. Some researchers say switching to dry powder inhalers may be as beneficial for the climate as an individual adopting a vegetarian diet.

One of the hospitals in Green’s network, St. Joseph’s Health Centre, found that conversations with patients led to a significant decrease in the use of metered-dose inhalers. Over the course of six months, the hospital went from 70% of patients using the puffers, to 30%.

Green says patients who switched to dry powder inhalers have largely stuck with them and appreciate using a device that is less likely to make conditions that inflame asthma worse in the long run.

Doctors like Divo are starting to bring those one-on-one conversations about more climate-friendly inhalers to patients in the U.S.

This segment aired on March 14, 2024.