Ever get the feeling you are being watched? How many cameras caught you on your way to work today? How many companies tracked your buying habits on your lunch break? Where is all this information about you going?

These may be obviously pertinent questions in the digital age, when 21st-Century technology gives corporations and institutions unprecedented access to our personal information, but they've been the subject of feverish concern for decades. Arguably it was during the 1970s, especially in the US, where the issue of surveillance and privacy really came into public focus for the first time. The decade's political scandals provided such an increase in awareness surrounding these issues that they quickly filtered into popular culture, especially cinema.

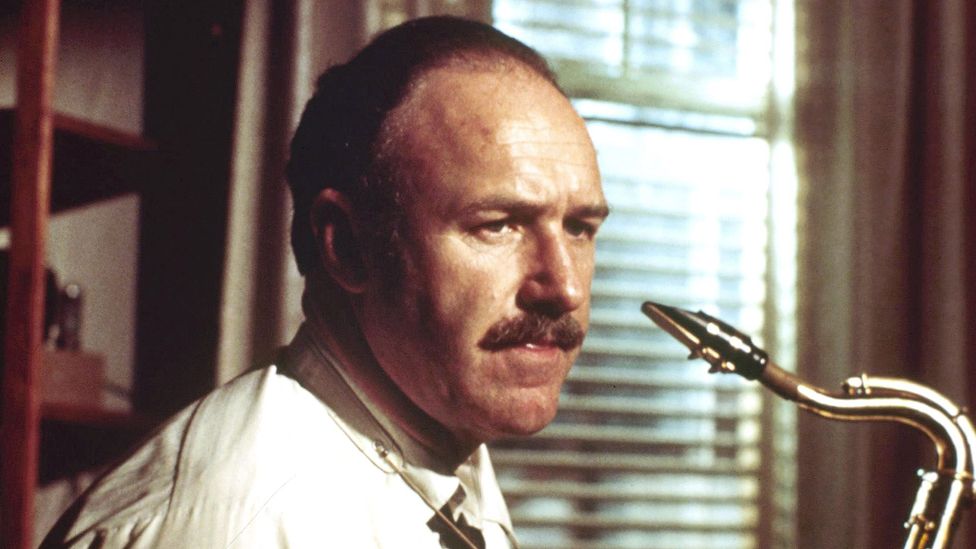

Gene Hackman plays a skilled wiretapper – using equipment that was very close to reality (Credit: Alamy)

American New Wave cinema – the movement of young, maverick directors who reshaped the film industry from the mid-1960s – was especially concerned with these themes. From Alan J Pakula's Klute (1971) and The Parallax View (1974), to Sydney Pollack's Three Days of the Condor (1975), US thrillers gained a paranoid edge. Arguably the most effective and evocative of all these was Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation (1974), released 50 years ago this week.

The Conversation follows Harry Caul (Gene Hackman), a skilled private surveillance expert. He is tasked by a shadowy client, known to him as "the Director" (Robert Duvall), with the difficult job of recording the conversation of a couple walking around the bustling Union Square in San Francisco, meticulously taping what he suspects is an affair.

The slowness and sharp but low-key focus of the film is a remarkable shift in tone from the emotion and drama of Coppola's The Godfather – Lucy Bolton

Caul grapples with ethical dilemmas as he navigates the murky world of his profession. As he edits his tape, he worries that he is being used for purposes other than mere surveillance, eventually refusing to hand over his work to the Director's underling Martin Stett (Harrison Ford). Believing from what he hears on the recording that there may be a plot to murder the couple – one half of which is the adulterous wife of the Director (Cindy Williams) – he grows paranoid about being surveilled himself. Caul's guilt and obsession intensifies, leading to a breakdown of his personal and professional life: he is also haunted by a death caused by his work on an earlier case.

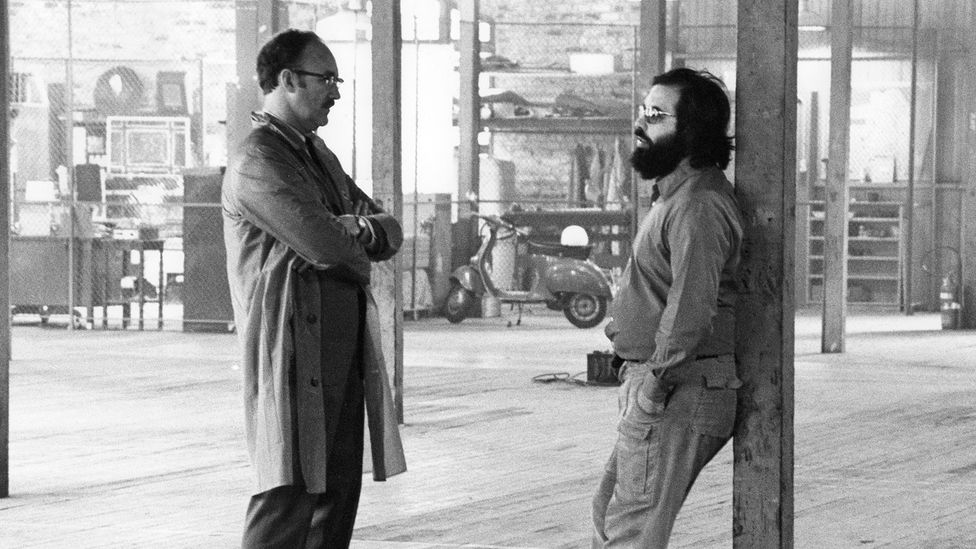

Amid what was a remarkable period for Francis Ford Coppola, with the success of The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather: Part II (1974), The Conversation was really his passion project. As Professor Lucy Bolton, a specialist in Film Philosophy at Queen Mary, University of London, suggests, this was "Coppola's chance to make a personal, intimate and intellectual work. He didn't actually want to make The Godfather: Part II, but agreed to so that he could make The Conversation. The slowness and sharp but low-key focus of the film is a remarkable shift in tone from the emotion and drama of The Godfather."

Filming it in between those two more famous films, Coppola masterfully crafted a taut psychological thriller that has as much to say about today's climate of surveillance as it does about its era of production – albeit with the interesting contrast between the analogue then and the digital now.

The paranoid climate of the time

The US in the early 70s still bore the scars of the political turmoil of the previous decade, one defined by assassinations, riots and an increasing awareness of the technology and techniques deployed by the state's secret services. Cinema had already tapped into the latter phenomenon, with films such as John Frankenheimer's The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and Seven Days in May (1964) channelling a growing societal paranoia into thrilling drama.

Francis Ford Coppola with Hackman on set – the film came in the middle of a remarkable period for the director (Credit: Getty Images)

Yet US cinema of the early 1970s further dialled up such paranoia, supercharged especially by the momentum of the Watergate scandal – the fallout from a 1972 break-in at Democrat Headquarters in the Watergate Building, Washington DC, and the subsequent attempt by the Richard Nixon administration to cover up their involvement. With the revelations that they had been spying on their political opponents using phone-tapping, among other things – information that required thriller-like manoeuvring to uncover by journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, eventually dramatised by Pakula in All the President's Men (1976) – the American New Wave became obsessed with the possibilities of this new surveilled US.

More like this:

- Why The Godfather was a stark warning for the US

- The enduring draw of the Watergate scandal

- How a microbudget student film changed sci-fi forever

Coppola's film is arguably the strongest of the small movement of films anticipating and responding to Watergate because it really understands the atmosphere of the time and what the possibility of being spied on does to people. "The backdrop of the film is the growing paranoia about surveillance generally, and the film's release captures the mood of the time in the midst of the Watergate scandal," says Dr Dan Lomas of the University of Nottingham, an Assistant Professor in International Relations with a background in Intelligence & Security Studies. It was partly luck that the film was in the right place at the right time, however. "Of course," Lomas continues, "links to Watergate are coincidental. Coppola is filming in autumn 1972 to early 1973, and the filming ends just as the real scandal of Watergate starts to get political attention, but the film's release in April 1974 is really in the midst of the national scandal." Nixon resigned as president a few months later, in August 1974.

Bolton also agrees that The Conversation both foreshadowed and encapsulated the Watergate era. "The film has inevitably gained associations with Watergate because of the timing, the theme of covert surveillance, and indeed the equipment that Caul uses," she echoes, "but in fact the film was well underway before the Watergate scandal broke. So, it's interesting to think of how the film was so in touch with the zeitgeist, and the timing of its release consolidated it as a work that's emblematic of the period's paranoia."

I think the film certainly does live on because of the wider fear of so-called 'surveillance capitalism' and the growth and influence of the private tech sector – Dan Lomas

The film's psychological drama, not to mention its realism, is especially aided by the soundscape constructed by Walter Murch, who was nominated for an Oscar for best sound mixing for the film, and would go on to win with his work on another Coppola film, Apocalypse Now (1979), when he also became the first person to receive the film credit of sound designer. The sound technology used throughout the film was unnervingly similar to that associated with the period's real scandals. "Coppola admitted his shock that some of the equipment used in the film mirrored the Watergate scandal and modern-day surveillance practices in the US [more generally]," Lomas explains.

How it resonates now

With 21st-Century hindsight, the paranoia of The Conversation does feel somewhat ironic. After all, we have never been happier to hand over the kind of information that someone like Harry Caul went to great pains to obtain. Aside from us willingly volunteering such information, digital technology has also provided easier means for us to be surveilled compared to Caul's complicated analogue set-up. In 2019, documents published by Wikileaks that appeared to be from the CIA's Center for Cyber Intelligence detailed a project in which the organisation could potentially hack a Samsung F8000 smart TV set, allowing for microphones to listen in while the television appeared off. The Weeping Angel project, as it was codenamed, broke as a story but then seemed to disappear. Being watched and listened to is now so utterly normal that it warranted little more than a collective shrug.

The Watergate scandal, which ended in Nixon's resignation, made the film seem right on-the-money (Credit: Getty Images)

The idea of surveillance deployed in homes in such everyday circumstances recalls the final scene in Coppola's film. Caul receives a threatening phone call in which it is revealed that his flat has been bugged. The final scenes show him taking apart the flat in his search for the potential device but to no avail, eventually sitting among the ruins of his room mournfully playing his saxophone. While there's some ambiguity as to whether the bug is be in the saxophone itself, or the whole scene is in fact a delusion, the effect on the character is the same, triggering a breakdown in him. It is not potential surveillance in the pursuit of information; it is surveillance as threat. Yet, would Caul have been that bothered by the same threat in 2024?

"It's interesting to see the analogue mechanics of the technology [in the film] and how successful it is," Bolton aptly suggests, "but compared to the level of surveillance that we are all under today it seems primitive and low-key. When we think about the facial recognition systems in shopping centres and the GPS tracking enabled by our phones, we are surveilled to a degree that would be unimaginable to Caul. The Conversation serves to highlight the magnitude of invasiveness that is surveillance, and the possibilities of misinterpretation, and the acquisition by bad actors. These themes could not be more relevant to our current situation."

Perhaps this is why the film has aged so well: its paranoia highlights our surprising acceptance of far greater levels of modern surveillance. Lomas also believes that in some ways the film has only become more pertinent than it was in 1974, because the private technology sector, which Harry Caul does somewhat represent in the film, has arguably become so powerful and dominant in the digital age. "I think the film certainly does live on because of the wider fear of so-called 'surveillance capitalism' and the growth and influence of the private tech sector," he says. "The real enemy in the film isn't the CIA or FBI: the enemy is the private sector who put morals and ethics aside for the sake of profit. Today, we see that all aspects of our lives can be monitored by the private sector. Your data is a commodity that's passed on to others, and, for all the concern about state surveillance, it's private tech that's the issue."

Perhaps, then, a small dose of Harry Caul's cynicism wouldn't go amiss in the digital age, as unseen eyes watch on, ears listen in and the detail of our lives is continually gathered for purposes unknown.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on X.