Originally a convent dating to the 13th century, and once a reformatory for prostitutes, the Giudecca women’s prison, set on an island in the Venetian lagoon, will this summer perform a quite different role: as the official pavilion for the Vatican at this year’s Venice Biennale.

Pope Francis is due to attend on 28 April – the first pontifical visit to the Biennale since it was founded in 1895. In the women’s prison he will see a work by Maurizio Cattelan, who notoriously created a hyper-real sculpture in 1999 depicting Pope John Paul II struck down by a meteorite.

For this exhibition, however, the Italian-born artist is contributing a work to be displayed on the facade of the prison chapel. Referencing Andrea Mantegna’s painting Lamentation Over the Dead Christ, it is a large-scale photograph of his own dirty, dusty feet.

Leading one of the first tours around the prison, which can be booked by members of the public, were three inmates, dressed in striking uniforms of navy and white that they had designed and made in the prison’s workshops. They introduced themselves only by their first names – Silvia, Emanuela and Paola.

After an introduction to the prison, Emanuela, a middle-aged woman with neat jewellery and a confident manner, took the group through to the first venue for art: the staff bar, which, with its bottles of Select and Aperol, could have been any bar in the city, albeit with somewhat cheaper price points.

On the walls are displayed radical poster works by Corita Kent, with graphic messages protesting against war and violence. Kent, who died in 1986 and is the only deceased artist featured in the show, spent part of her life as a nun.

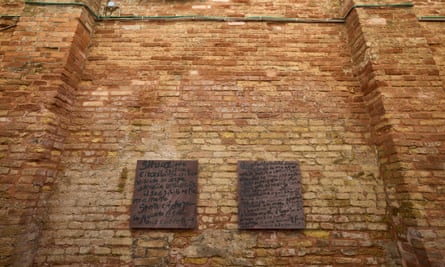

Silvia took the lead as guests entered a long, narrow walkway between the prison buildings and its outer walls. The sides are lined with glazed lava stone slabs, painted by the artist Simone Fattal with excerpts of poems written by the prisoners. “Our feelings are written here; a piece of us is written on these works of art,” said Emanuela. On the end wall of the walkway, below a lookout post, was a work by Claire Fontaine, a Palermo-based art collective. Depicting a large eye with a stroke through it, it conveyed “the blindness of society”, said Paola, “what people don’t look at and what they don’t want to see”.

The tour continued past a large, lush vegetable garden thick with fruit trees and rows of artichoke plants. Working here, said Emanuela, “we can dream of other things; we can almost forget we are in prison”. The next stop was a wide open courtyard. A few inmates clustered beside a medieval well looked on as Emanuela explained a second Claire Fontaine work, a large neon text piece fixed to one of the walls reading: “Siamo con voi nella notte” – “We are with you in the night” – “which speaks to us as a message of solidarity from the people outside,” she said.

The tour then trooped through the visitors’ room, to a space in which a short film by the artist Marco Perego and his wife, the actor Zoë Saldaña, was being shown. Saldaña, who starred in James Cameron’s Avatar films, acted alongside inmates in a narrative about a prisoner on the day of her release. Describing the process, she saidthe work was meant “not so much like a documentary that has to be truthful – instead we encouraged [the inmates] to make a piece of art with us”.

The pavilion was commissioned by Cardinal José Tolentino de Mendonça, who runs the Vatican’s dicastery for culture and education. The co-curators Bruno Racine and Chiara Parisi took on the Vatican pavilion “on the basis of perfect trust with the cardinal, who is himself a renowned poet”, said Racine, a former director of the National Library of France. “He understands the psychology of an artist and the desire for autonomy and not to be subject to the influence of ideas from outside.”

Asked whether she was a Roman Catholic, one of the artists involved in the project, the French hip-hop choreographer Bintou Dembélé, laughed. “My religion is the street,” she said.