The Hidden Wisdom of Cookbooks

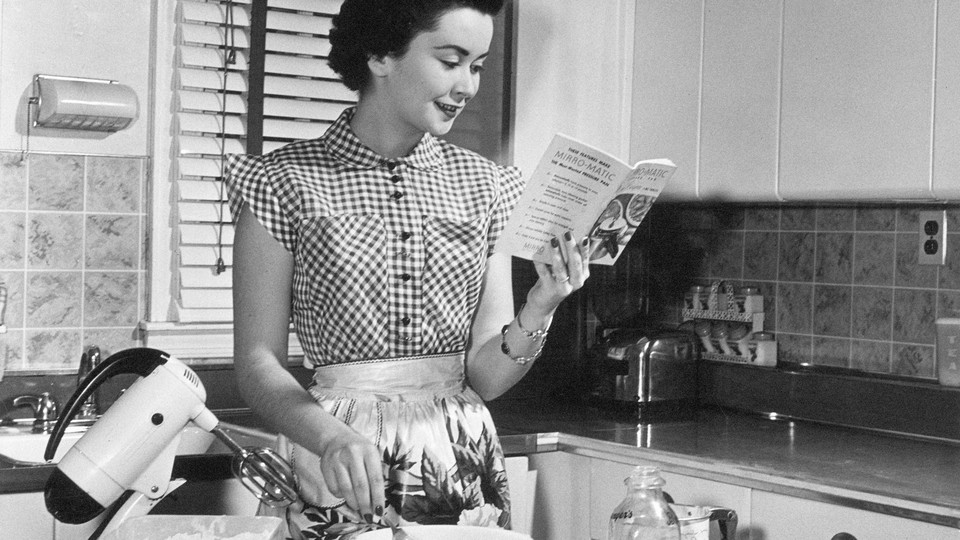

The author Ruby Tandoh argues for the freedom to cook—and eat—for pleasure.

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

The fact that I live close to a dedicated cookbook-and-food-writing store—and that it’s one door down from a specialty market full of bread, cheeses, and confections—is a constant delight, though a mild threat to my household’s financial security. Strolling down this block can create moments of gorgeous culinary serendipity: I’ll spin through the bookshop, Bold Fork Books, drinking in an assortment of colorful food photography and picturing the sensory bouquet of each dish—and perhaps picking up another hardcover to add to my already overstuffed shelves. Then I’ll head over to Each Peach, where I can admire the rows of glistening preserves and tinned fishes, smell the sandwiches being prepared, and bring home crusty bread, a bottle of wine, and some seasonal vegetable or another.

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

For me, cookbooks generally provide more inspiration than instruction. I’ll pick one up, leaf through it, and set off on my own adventure, leaving the recipes behind. They’ve given me a rotation of dinners I make by heart and eye, leaving out ingredients I don’t care for and techniques I find too fussy (I always skip the julienned, fried leeks in the New York Times recipe for creamy leek pasta, though they probably do make the dish nicer). But lately, I’ve been thinking back to my earliest days as a home chef, when I would sit down and read cookbooks all the way through, looking for recipes to try and marking techniques to practice. This week, Marian Bull argues for that method by recommending eight cookbooks worth moving through cover to cover, for the quality of their instructions and their prose. A reader “might flag recipes they want to cook, or they might not,” she writes. “The point of this practice is pleasure, not pragmatism.”

Bull mentions Samin Nosrat’s Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat—a book that radically changed my cooking by teaching me how to control flavor—and Ruby Tandoh’s Cook as You Are, which also holds a treasured spot on my shelf. But her list put me in mind of another piece of food writing I love: Tandoh’s earlier book Eat Up!, a manifesto arguing for our right to eat for pleasure and connection instead of for utilitarian calorie delivery. Tandoh came into my life when she was a young, charming university student on The Great British Bake Off, in 2013. But she became a role model for me in my own college days after she came out as queer, and wrote honestly and sensitively about her eating disorder. Eat Up! is a distillation of her philosophy, one I still hold dear: that there’s no perfect way to eat, that a normal appetite ebbs and flows, that food is important for its experiential value just as much as for its nutritional value. The book contains short, warm recipes for dishes Tandoh finds especially cozy, interspersed between her investigations into food’s connections with sexuality, different cultures’ eating taboos, and the history of wellness.

I haven’t returned to Eat Up! in a while. But its lessons are still with me when I impulsively decide I want a scrambled egg in a scallion pancake for breakfast, or when I prepare an emergency chickpea curry for a heartbroken friend at her apartment. With the right attitude, the daily required drudgery of making meals can become a way to show love, learn more about one another, and experience joy.

Eight Cookbooks Worth Reading Cover to Cover

By Marian Bull

Flag dishes you want to make, or don’t: The point of this practice is pleasure, not pragmatism.

What to Read

If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho, by Sappho, translated by Anne Carson

Hardly any of Sappho’s work survives, and the fragments scholars have salvaged from tattered papyrus and other ancient texts can be collected in thin volumes easily tossed into tote bags. Still, Carson’s translation immediately makes clear why those scholars went to so much effort. Sappho famously describes the devastation of seeing one’s beloved, when “tongue breaks and thin / fire is racing under skin”; the god Eros, in another poem, is a “sweetbitter unmanageable creature who steals in.” Other poems provide crisp images from the sixth century B.C.E.—one fragment reads, in its entirety: “the feet / by spangled straps covered / beautiful Lydian work.” Taken together, the fragments are sensual and floral, reminiscent of springtime; they evoke soft pillows and sleepless nights, violets in women’s laps, wedding celebrations—and desire, always desire. Because the poems are so brief, they’re perfect for outdoor reading and its many distractions. Even the white space on the pages is thought-provoking. Carson includes brackets throughout to indicate destroyed papyrus or illegible letters in the original source, and the gaps they create allow space for rumination or moments of inattention while one lies on a blanket on a warm day. — Chelsea Leu

From our list: Seven books to read in the sunshine

Out Next Week

📚 I Just Keep Talking, by Nell Irvin Painter

📚 Funny Story, by Emily Henry

📚 A Body Made of Glass, by Caroline Crampton

Your Weekend Read

Something Weird Is Happening With Caesar Salads

By Ellen Cushing

We are living through an age of unchecked Caesar-salad fraud. Putative Caesars are dressed with yogurt or miso or tequila or lemongrass; they are served with zucchini, orange zest, pig ear, kimchi, poached duck egg, roasted fennel, fried chickpeas, buffalo-cauliflower fritters, tōgarashi-dusted rice crackers. They are missing anchovies, or croutons, or even lettuce. In October, the food magazine Delicious posted a list of “Caesar” recipes that included variations with bacon, maple syrup, and celery; asparagus, fava beans, smoked trout, and dill; and tandoori prawns, prosciutto, kale chips, and mung-bean sprouts. The so-called Caesar at Kitchen Mouse Cafe, in Los Angeles, includes “pickled carrot, radish & coriander seeds, garlicky croutons, crispy oyster mushrooms, lemon dressing.”

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.