There seems little doubt that Taylor Swift's new album, The Tortured Poets Department, was written as a form of catharsis. At a show in Melbourne in February, she described it as a "lifeline". "Just the things I was going through and the things I was writing about – it kind of reminded me of why songwriting is something that actually gets me through my life," she said. "I never had an album where I needed songwriting more than I needed it on Tortured Poets." In its review, Rolling Stone argues that it is the most personal of her whole career.

Unless you've been hiding under a rock, you'll know at least some of the rumours: that it handles the end of her six-year relationship with the actor Joe Alwyn, her short-lived fling with The 1975 singer Matty Healey, and her current romance with American footballer Travis Kelce. There are suggestions of depression, betrayal, and a broken engagement.

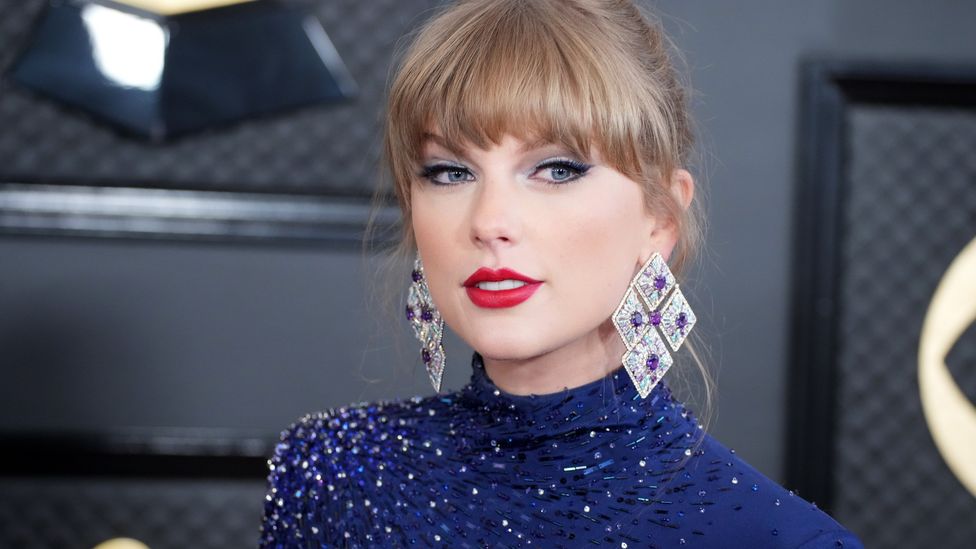

Some of the knee-jerk responses to Swift's music may say more about our culture of misogyny than her songwriting talent

Should this speculation change the way we interpret her songs? Critics have sometimes dismissed Swift's "confessional" style of songwriting as little more than fodder for tabloid gossip. Yet the title of her new album surely nods to the millennia-old tradition of writers who have turned their heartbreak into art (even if it also puns on the name of Alwyn's WhatsApp group).

Debates around the autobiographical inspiration of art have, after all, circled some of the greatest pieces of literature, and some of the knee-jerk responses to Swift's music may say more about our culture of misogyny than her songwriting talent.

Truth or fiction?

Sappho, a lyric poet writing in Ancient Greece around 2,600 years ago, may be the archetypical tortured poet. Her work, which would have been set to music, was so popular in the ancient world that she was sometimes known as the "10th muse". Few of her poems survive, but from the fragments that remain, we see heart-rending explorations of affairs with both men and women:

I simply want to be dead.

Weeping she left me

with many tears and said this:

Oh how badly things have turned out for us.

Sappho, I swear, against my will I leave you.

We simply cannot know whether this was a response to a real relationship, though historical records suggest that many ancient readers assumed that the poems were autobiographical. This uncertainty has not diminished her reputation as the original lovestruck poet: according to legend, she leapt from a cliff to her death, after having been spurned by her lover – a scene that has inspired countless artworks and poems over the centuries.

Sappho, a lyric poet writing in Ancient Greece around 2,600 years ago, may be the archetypical tortured poet (Credit: Getty Images)

We can see similar speculation around the poetry of Petrarch (1304-1374), whose Canzoniere (songbook) charts his anguish at his unrequited feelings for a figure named Laura across a period of 40 years.

"Love found me with no armour for the fight/ My eyes an open highway to the heart," he wrote upon first seeing her. Laura has been taken as a fictional creation by Petrarch's contemporaries and later scholars. The poet himself, however, was adamant that she existed and that his heartache was real. "I wish indeed that you were joking about this particular subject," he wrote to his friend Giacomo Colonna, "and that she indeed had been a fiction and not a madness."

Much ink and paper might have been spared if any of Shakespeare's correspondence had similarly survived. The apparent love triangle in the "dark lady" and "fair youth" sequence of sonnets has been the subject of endless conjecture about the potential identities of these figures and the nature of their relationships with the Bard.

'Thinly disguised' facts

The rise of mass media in the 20th and 21st Centuries has only amplified speculation about the inspiration of modern writers.

Bob Dylan furiously denied mining his personal experiences. Many critics assumed that Blood on the Tracks, from 1975, had laid bare the disintegration of his marriage to Sara Lownds. "I don't write confessional songs," he later wrote in the notes accompanying a career-spanning box set. "It only seems so, like it seems that Laurence Olivier is Hamlet." In interviews, however, he has conceded that some of his emotional turmoil may have bled into the lyrics, while a former girlfriend claims that You're Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go is about their relationship during this period.

More like this

- The real meaning of the song 'Slut'

- The return of a pop music masterpiece

- How Joni Mitchell forged a path for Taylor Swift

Others, such as Joni Mitchell, were more willing to admit the autobiographical nature of their work. "I felt like a cellophane wrapper on a pack of cigarettes," she famously said about the writing of her album Blue (1971). "I felt like I had absolutely no secrets from the world and I couldn't pretend in my life to be strong. Or to be happy. But the advantage of it in the music was that there were no defences there either."

Such positive attitudes have not always been shared by critics, who see a tension between authenticity and artistic credibility. Some believe that an overreliance on personal experience devalues the writer's creative talent. These arguments are often levelled at women more than men, and they may carry the whiff of sexism.

Joni Mitchell has admitted that her 1971 album, Blue was autobiographical (Credit: Getty Images)

Nora Ephron noted as much in an essay on her book Heartburn, published in 1983. The novel was inspired by her former-husband Carl Bernstein's affair with the "unbelievably tall" wife of a British diplomat, while Ephron was heavily pregnant with their second child.

"I've noticed, over the years, that the words 'thinly disguised' are applied mostly to books written by women," she wrote. "Let's face it, Philip Roth and John Updike picked away at the carcasses of their early marriages in book after book, but to the best of my knowledge they were never hit with the 'thinly disguised' thing."

'Slut-shaming'

Swift, of course, has actively encouraged speculation about the inspiration behind her songs with numerous hidden clues and "Easter eggs", which has invited ire from journalists in the past. "Taylor Swift kisses and tells... and goes too far," The Atlantic opined in 2010. A blog for The Paris Review took a similar view, describing her craft as "the perfected realisation of every writer's narrowest dream: to get back at those who had wronged us, sharply and loudly, and then to be able to cry innocent that our intentions were anything other than poetic and pure".

She has nothing to prove at this point – Natasha Lunn

Like Ephron, Swift has balked at attempts to reduce her output to the songs' autobiographical content. "In the years preceding this, I had become the target of slut-shaming – the intensity and relentlessness of which would be criticised and called out if it happened today," she wrote around the recent re-recording of her album 1989, which came out in 2014. "The jokes about my amount of boyfriends. The trivialisation of my songwriting as if it were a predatory act of a boy crazy psychopath. The media co-signing of this narrative. I had to make it stop because it was starting to really hurt."

Natasha Lunn, author of Conversations on Love and a writer for the Swiftian Theory newsletter, argues that Swift is now reclaiming the narrative. "To me there is something powerful about her stepping into this moment so confidently, and not being afraid that writing a breakup album will mean some critiques undermine her songwriting skills," Lunn says. "She has nothing to prove at this point."

In Lunn's view, we should appreciate the talent that is required to dissect the complexities of romance. "She has a knack of taking her very personal experience of heartbreak, sharing it in a raw and beautifully crafted way with the world, and giving us all permission to feel things we might previously have been ashamed of."

The reviews so far have been positive. The site Metacritic, which aggregates ratings across media, gives The Tortured Poets Department an average score of 84 out of 100, which it judges to be "universal acclaim". One specific criticism concerns the consistency of the material, with some feeling that the songs were of uneven quality, particularly in the extended "Anthology" edition that includes 15 additional tracks.

"The feverish Tortured Poets Department is a full-throated return to her specialty: autobiographical and sometimes spiteful tales of heartbreak, full of detailed, referential lyrics that her fans will delight in decoding," Lindsay Zoladz wrote in a generally positive review for The New York Times. She conceded, however, that "great poets know how to condense, or at least how to edit. The sharpest moments of The Tortured Poets Department would be even more piercing in the absence of excess, but instead the clutter lingers, while Swift holds an unlit match."

Some reviewers have also expressed disappointment at the lack of experimentation in the album's production, with The Guardian's Laura Snapes concluding that it beats "a bruised retreat that structurally confines the lacerating lyrics".

Swift has actively encouraged speculation about the inspiration behind her songs with numerous clues (Credit Getty Images)

Swift is thought to have shaped the album's lyrical content around the "five stages of grief" – a theory first introduced by the Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in the 1960s. In the run-up to the album's release, Swift compiled five playlists from her back catalogue, each representing a different stage – anger, denial, bargaining, depression and acceptance. And it is easy to hear these recurring themes in the latest songs, from the confused denial of Fortnight to the rage of The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived and the quiet sadness of loml.

Many of the lyrics – Fresh Out the Slammer, in particular – are layered with images of claustrophobia and confinement. But Swift elevates her heartache with humour – My Boy Only Breaks His Favourite Toys is surely one of her wittiest songs – and characteristic self-awareness. It seems hard to deny that her nod to the "tortured poets" is tinged with irony when she sings: "I laughed in your face and said/ You're not Dylan Thomas, I'm not Patti Smith/ This ain't the Chelsea Hotel, we'rе modern idiots".

Yet there are also plenty of literary allusions that deserve to be read seriously, from the biblical imagery in Guilty as Sin? to the legend of Cassandra in the track of the same name. And it could be that she's referencing Sisyphus's endless punishment in So Long, London: "My spine split from carrying us up the hill." His plight would seem the perfect analogy for someone who feels that they are in a constant struggle to keep a problematic relationship alive.

One of the standout tracks, The Prophecy, appears on the extended cut of the album. This prayer for everlasting love bears an uncanny resemblance to Sappho's Ode to Aphrodite – her only poem to survive in full. Whether or not the details in either work can be taken literally, they surely express real feelings that both women had experienced. It's amusing – and reassuring – to imagine scholars pondering the few lasting fragments of Swift's poetry in two-and-a-half millennia from now, when all the hot takes and tabloid columns about her personal life have been lost to time; when – as Swift sings in the final track of the anthology – "the only thing that's left is the manuscript".

David Robson is an award-winning science writer and author. His next book is The Laws of Connection: 13 Social Strategies That Will Transform Your Life. It will be published by Canongate (UK) and Pegasus Books (USA & Canada) in June 2024. He is @d_a_robson on X and @davidarobson on Instagram and Threads.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.