Thirty years ago, in April 1994, Nelson Mandela emerged victorious in South Africa's first democratic elections. This epochal moment marked the ultimate defeat of the racist apartheid system, which South African musicians had long decried in their art. In a sense, Mandela's triumph was foreshadowed by a song released 14 years previously, in 1980, which promised "better days" to a country that desperately needed them.

The song was Paradise Road, performed by the black female group Joy, which topped South Africa's pop charts for a staggering nine consecutive weeks. Written and composed by two white South Africans, Patric van Blerk and the late Fransua Roos, Paradise Road is often touted as one of the best South African songs of all time, and even an "unofficial" national anthem.

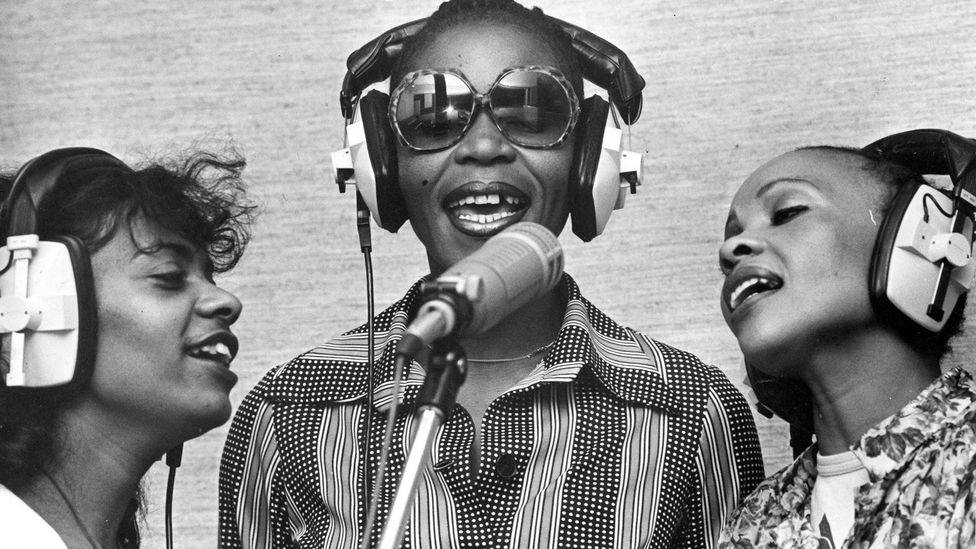

Patric van Blerk was already an industry veteran by the time he was introduced to Joy in the late 1970s. He had worked closely with the iconic Margaret Singana, known by the moniker "Lady Africa", who starred in the musical Ipi Tombi in the West End and on Broadway. Van Blerk also launched the boyband Rabbitt, co-writing their single Charlie, which was a hit on the South African charts. He was introduced to Joy by their manager, Linda Bernhardt, at a time when the girl group – Anneline Malebo, Thoko Ndlozi, and Felicia Marion – were eager to diversify from their usual repertoire of Motown covers and establish themselves as serious recording artists. Invited to write for them, Van Blerk and his long-term writing partner Roos offered the trio a selection of songs. "Paradise Road stood out like Table Mountain," Van Blerk tells the BBC.

However, Marion, Joy's only surviving member, was underwhelmed. "Fransua began to play on the keyboard and I thought, 'well, how boring!'" she tells the BBC, disappointed that she was instructed to sing the melody exactly as written. "I guess I wanted to do a lot more frills and riffs. It was too simple for me." But the songwriters knew there was magic in Paradise Road, enlisting esteemed jazz ensemble Spirits Rejoice for the recording.

As the song started, the crowd went mad. Something just sent them into a frenzy – Felicia Marion

The song begins with Marion's breezy soprano, inviting the listener to "come with me, down Paradise Road". As she extends her bewitching offer, Malebo and Ndlozi enter the mix, cooing softly in the background. Malebo takes the reins at the anthemic chorus, belting triumphantly that "there are better days before us and a burning bridge behind us". The song's stirring lyric is buoyed by lavish, shimmering orchestration. "I said to Fransua, 'the song is just screaming for strings, for brass, especially French horns and harps,'" Van Blerk recalls, "and he just said: 'Cool. Well, let's do it!'" Marion remembers performing the song in a community hall on an unassuming Tuesday night in "either Sharpeville or Soshanguve" to an all-black crowd, before its official release. "As the song started, the crowd went mad," she says. "Something just sent them into a frenzy."

Yet the song almost flopped. "For the first four weeks, I could not get the record played in South Africa. Impossible!" Van Blerk says. He remembers a famous South African producer even telling him: "This is the biggest load of crap I've ever heard… you cannot use strings and brass and French horns and harps [on a black South African record]. It's unheard of."

But Van Blerk persisted. He presented the song to industry rival and radio personality David Gresham, who hosted a daily programme on the South African Broadcasting Corporation. "I thought it was the best song I'd heard in the whole year. I couldn't believe that such a great song had been turned down," Gresham tells the BBC, suggesting that commercial radio discriminated against the song on racial grounds. "I think they were anti-supporting South African music, maybe because [Joy] were not white artists", he says. Gresham proceeded to go "hell bent for leather" in playing Paradise Road relentlessly.

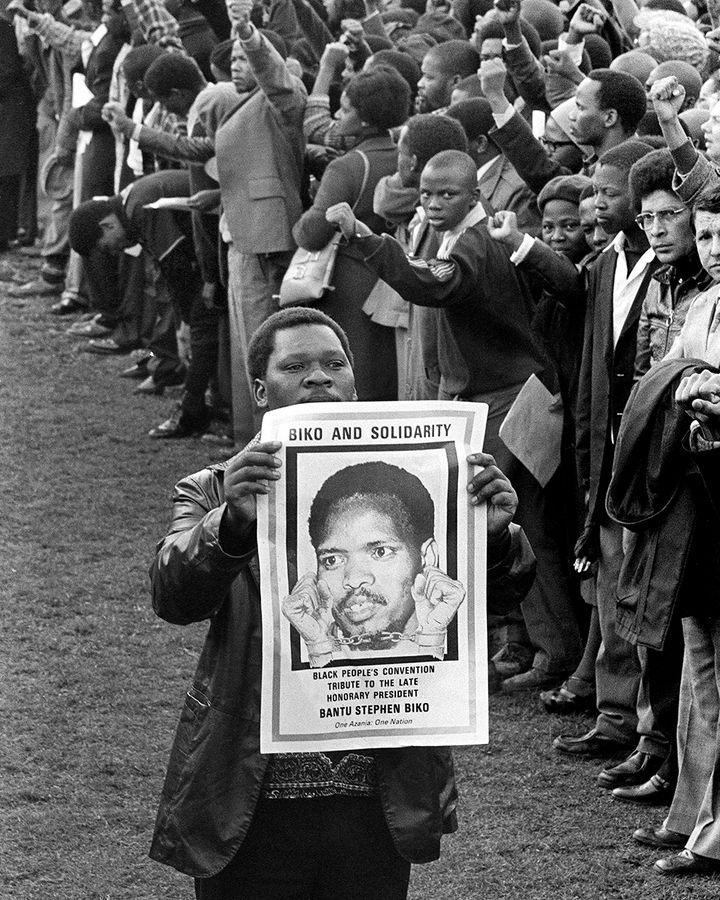

Protestors attend the funeral of the Black Consciousness Movement leader Steve Biko, who was killed in state custody in 1977 (Credit: Getty Images)

It became a huge hit. Paradise Road reached number one on South Africa's Springbok charts on 1 August 1980 – replacing Marti Webb's Take That Look Off Your Face – and stayed there for more than two months. According to this archive of South African chart history, Joy were the first and only black South African act to hit the top spot on the Springbok Radio charts. As Gwen Ansell writes in her book Soweto Blues, Paradise Road's crossover success demonstrated the "impossibility of maintaining strict divisions" between the music of South Africa's various communities. "The fact that the song attracted fans across all racial strata was a further kick to white supremacy," journalist Bongani Madondo wrote in the Daily Maverick. Joy went on to win two Sarie awards (South Africa's then-equivalent of the Grammys) for best vocal group and best English album. Van Blerk, Roos, and engineer Greg Cutler were also awarded.

More like this:

• Suavecito: The love song that became an anthem

• The 'black national anthem' born from a birthday party

• MLK Day: The song that changed the US

It is easy to understand why the song's cryptic but hopeful message resonated. The 1970s was a decade of escalating violence and repression in South Africa, epitomised by the Soweto Uprising of 1976, during which police gunned down protesting black schoolchildren with impunity. The following year, Black Consciousness Movement leader Steve Biko was killed in state custody. Unlike the explicitly anti-apartheid music of, say, Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba, Paradise Road didn't dwell on the injustices of the present but instead offered a prescient glimpse into a more peaceful future. Shimmy Jiyane of the Soweto Gospel Choir, who covered the song, tells the BBC that Paradise Road "became an anthem for the struggle [which] kept the spirit of the people going".

I did not sit down to write a political song. I did not sit down to write a preaching song… I just wrote what came – Patric van Blerk

However, Paradise Road was never conceived as a response to the miserable state of South African affairs. "I did not sit down to write a political song. I did not sit down to write a preaching song… I just wrote what came," Van Blerk says. "I've always been a very political creature. And I was very aware on every level of what was happening; it must have just seeped into my psyche and consciousness."

The song "[gave people] hope that one day they will be walking through Paradise Road," opined Ndlozi in a 1993 interview. Marion echoes this sentiment and notes how the song provided comfort to South Africa's political exiles. However, she concedes that, in certain ways, "these did not turn out to be the 'better days' that we had hoped for", citing high levels of crime, corruption, and unemployment in present-day South Africa.

'Seismic feeling'Attempts were made to make Paradise Road a hit internationally. Joy made their first British television appearance on Marti Caine's eponymous BBC show and embarked on a UK tour. Van Blerk remembers playing the song to a radio DJ in Birmingham. "After the song played, the presenter said to me, 'that is absolutely fantastic. What language are they singing in?'" Van Blerk sighs. "I [learnt] that certain non-South African ears could not really make sense of [Joy’s] diction. I was absolutely shocked, but it wasn't the first time that it rose up." In New York, Van Blerk's pitch to Cotillion Records was interrupted by the news that US President Ronald Reagan had been shot. A deal was never struck, and the song struggled to gain traction elsewhere.

Nelson Mandela's triumph in the April 1994 elections marked the defeat of South Africa's racist apartheid system (Credit: Getty Images)

Subsequent bids to heighten the song's profile outside South Africa were also unsuccessful. A version recorded by soul singer Dobie Gray for the 1988 film Hold My Hand I'm Dying was never released commercially. Discussions for artists like Dusty Springfield, Lulu, Cliff Richard and, much later, Josh Groban and Michael Bublé to cover the song never bore fruit.

Joy's star would not rise any further. The group disbanded in 1983 after Marion found her calling as a Christian and gospel singer. Both Malebo and Ndlozi went on to other musical ventures. Tragically, Malebo contracted HIV and died of Aids-related illnesses in 2002, aged 48. She used her final months to speak publicly about her status and challenge the stigma around HIV and Aids. Ndlozi died in January 2021, aged 74. The group will always be remembered in South Africa for the seismic feeling with which they delivered Paradise Road. More than 40 years since the song's release, it has become a standard, covered by numerous South African groups, and is still played on the radio to this day.

Van Blerk remains touched by the song's enduring popularity. "If I croak tomorrow, people will still be playing and singing Paradise Road," he says with a wink, "and that's a wonderful thought."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.