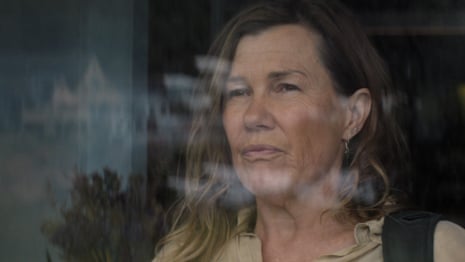

When Robyn Malcolm did a recent shoot for a magazine, they sent her through the proposed cover. She called them immediately. “I said, can you not do that to my face?”

Pushing against expectations for women to look and act a certain way – young, carefree, likable – has driven Malcolm her whole career, but especially since menopause. “They took notice, and they put me on the cover with everything as is. They said, ‘We just thought everyone liked that.’ Well, no, because I’m not here to make other women feel like shit.”

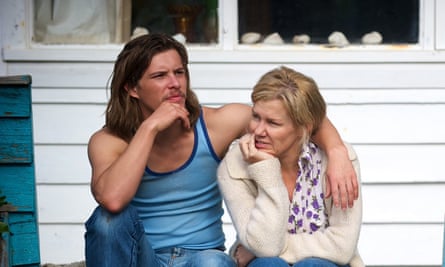

It’s partly the reason 59-year-old Malcolm – one of New Zealand’s best known and most beloved actors – co-created the new series she also stars in, After the Party. Last month, she won best actress at France’s Series Mania Forum for her role as Penny in the show. The character is a high school teacher who is the antithesis of a typical older woman on screen; an abrasive, unruly know-it-all. She tears strips off her students, bikes against the wind (it’s shot in New Zealand’s notoriously wild capital city, Wellington) and accuses her former partner, played by Scottish actor Peter Mullan, of sexually assaulting their teenage daughter’s friend. She makes frustrating decisions. In short, she acts like a real person.

“Women our age have lived a life, and have got quite angry,” Malcolm says. “They’re post-menopausal, so they’re in the middle of a whole storm of stuff. They’re not living in the middle of a happy ending.”

Many in New Zealand have been watching her on screen since they were kids – as nurse Ellen Crozier in Shortland Street, the country’s longest-running soap opera, as working-class mum Cheryl West in show Outrageous Fortune, in Australian shows Upper Middle Bogan and Rake.

Since before she was a single mum raising a baby and a toddler on the set of Outrageous Fortune – “It was a blur, I would get up at 4.30 to express milk in the dark, the only sound would be the pump like a vibrator, I was delirious” – Malcolm has always been a talker. She is, as she puts it, a “compulsive discloser”. When her son Charlie, now 20, was six, he gave her clear directives before entering his classroom. “He would say ‘No singing, no talking in accents and no holding hands’. And I said ‘Well what do I have left? That’s basically your mother’.”

She dealt with miscarriage, the strain of new motherhood and later menopause. The latter floored her with debilitating panic attacks. She made a 2022 documentary about those, You, Me and Anxiety, but was told not to focus on the menopause, lest it would alienate men. Instead, she channelled much of her experience into After the Party, dubbed “the best TV drama we’ve ever made,” by New Zealand pop culture website The Spinoff, airing on the ABC in Australia at the end of April, and Channel 4 in the UK later this year.

Malcolm grew up in the small South Island town of Ashburton, the oldest of four girls. Aged about 15, the classical music scholar began to feel restless. She marched against the 1981 Springbok rugby tour, got hit with a clod of dirt and got the hell out, which back then meant moving to Wellington. Her first job out of drama school was at the now defunct Downstage Theatre company, where then-artistic director Colin McColl recalls she could always do the “gruntier, grittier stuff”. She has only developed more depth, he says.

“She’s had knocks in her life … it’s this breadth of experience she brings to her work, all this history.”

Malcolm played a much-loved character for five years in hit local TV series Outrageous Fortune, winning multiple acting awards. But her star power was dented in 2010, when she led a handful of high-profile actors in arguing for better conditions on The Hobbit films, while Warner Bros warned they would be driven offshore. Then-prime minister John Key changed the law to disallow collective bargaining and the resulting public backlash against Malcolm saw her blacklisted locally. It’s still a sore point. “I lost work after that, there’s no doubt.”

In After the Party, Penny’s character is convinced she’s right, but she’s also vilified. Are there similarities? “It’s far easier to blame the woman. It’s far easier to say you know, ‘She’s hysterical,’ and the only way we can deal with her is by saying that she’s nuts.”

On set, Malcolm is “bold and argumentative, but only about the work,” says After the Party producer Helen Bowden, who was blown away by Malcolm and writer Dianne Taylor’s early scripts. Malcolm was heavily involved up until the filming, Bowden said. “On the day of the first shoot, she looked me in the eye and said, ‘I’m only doing one job during this shoot, which is being Penny.’”

This commitment was tested halfway through, when Malcolm tore her MCL ligament kayaking. “We were out in the Cook Strait and I was battling this huge sea and because I was so full of adrenaline I didn’t know what was happening, and when I got back I couldn’t walk,” Malcolm says. Her answer: for Penny to develop a limp.

In the show, one of Penny’s students wants to drop out, because what’s the point if the world is dying? It is something that weighs on Malcolm’s mind. “I don’t know how you can be a Kiwi and not be an environmentalist. It staggers me when people aren’t, because this country has been so beautiful and we’re watching it fall apart,” Malcolm says.

She gardens, drives an electric car and lives in a small house, but points out she’s just flown to France. “I struggle with this, and I cross my fingers that I’m doing enough, which I know I’m not.”

What she can do is write a new work. “Storytelling is so important. There’s this magical thing that happens between you and a piece of art, and that can connect us all.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion