What Is Wagner Doing in Africa?

Russian mercenaries are wringing wealth and political leverage out of the Sahel.

The videos began appearing on Telegram in November. One showed a pair of white mercenaries raising a black flag emblazoned with a white skull over a mud-brick fort in the Malian-desert outpost of Kidal. In another, a bearded white soldier moved through the town on a motorcycle, weaving among locals who chanted, “Mali! Mali!”

The troops belonged to the Wagner Group, the Russian mercenary outfit founded by Yevgeny Prigozhin a decade ago and best known for its role in Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Now reportedly under the control of a Russian military-intelligence unit, Wagner troops are showing up in impoverished countries within and just south of the Sahel region of Central Africa.

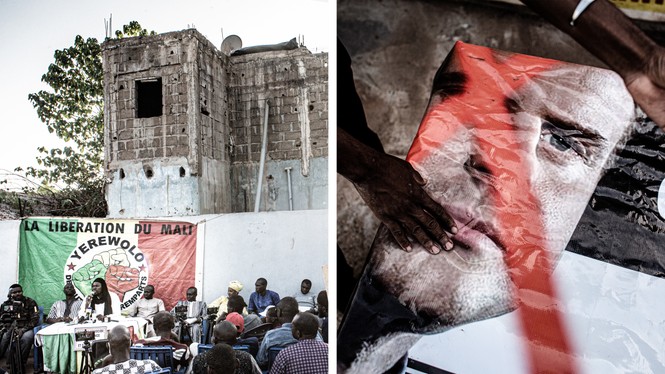

Most of Wagner’s clients in the Sahel are former French colonies, and all have been struggling for years against Islamist terrorists and other insurgent groups. For a decade, the French, with some support from the United Nations and the United States, took the lead in battling jihadists in the Sahel. But one by one, the military juntas that run these countries have booted out the French and the multilateral peacekeepers and hired Wagner, or, as its Sahel branch has renamed itself, Africa Corps.

Some of the Russian fighters got their start protecting commercial vessels from Somali pirates in the Gulf of Aden and battling the Islamic State in Syria a decade ago. Now they are tools in a great geopolitical realignment: Onetime client states of Western liberal democracies have repudiated their former colonizers and embraced Wagner, giving Russia political leverage across Africa—as well as new sources of wealth, including gold mines, as it pursues its war in Ukraine.

White mercenaries have propped up—or brought down—beleaguered African regimes in the past, but Wagner is different. It has direct ties to a national government with expansive geopolitical ambitions. And as Wagner grows its presence in Africa, it is forcing imperiled governments to make a Faustian bargain: The regimes get help in putting down the insurgencies that threaten their existence, but in return, they’re compelled to surrender a measure of their sovereignty and resources to a foreign army that heeds no laws except its own.

Prigozhin’s soldiers first showed up in Africa in 2017. They trained troops for the Sudanese dictator Omar al-Bashir, who was overthrown two years later. In Libya, they backed the rebel commander Khalifa Haftar, whose Libyan National Army is struggling for power and territory against the internationally recognized government in Tripoli. The Central African Republic, an impoverished former French colony just south of the Sahel, invited about 1,000 Wagner fighters to help stanch a rebellion in 2018. Within three years, they had taken back a good deal of territory and stopped a rebel advance on the capital. In the process, Wagner troops seized a Canadian-owned gold mine, Ndassima. The U.S. Treasury Department valued the gold deposits there at more than $1 billion, and John Lechner, the author of the forthcoming Death Is Our Business: Russian Mercenaries in the New Era of Private Warfare, says the mine is ramping up operations and could soon generate “about $100 million a year” for the mercenaries.

Then came Mali. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, a jihadist group operating in the Sahara and the Sahel, had allied with a faction of Tuareg separatists and taken over two-thirds of the country in April 2012. French troops set about dislodging the militants in January 2013, driving the jihadists from Timbuktu, Gao, Kidal, and other northern population centers into the surrounding desert and killing hundreds in a week-long battle that February. For the next decade, a French counterinsurgency force based in Chad precision-bombed al-Qaeda encampments deep in the Sahara.

But the French could never fully eradicate the jihadists. Many Islamist fighters fled to villages in the south. The French focused on aerial bombardments in the north, leaving poorly trained Malian troops to raid villages and take hundreds of casualties. The Malians resented this division of labor, and the ground operation made little progress.

Meanwhile, the Tuareg separatists, most of them secular insurgents, had moved back into Kidal with the tacit acceptance of the French. They sometimes assisted the French with intelligence to target the jihadists, and the Malians believed that the French were therefore protecting them. Kamissa Camara, Mali’s foreign minister from 2018 to 2020, told me that the dispute was one reason, by 2020, “the relationship between the French and the government was at an all-time low.”

Mali’s democratically elected government was toppled by a coup in August 2020, and old allegiances fell by the wayside. Few members of the junta that came to power had studied in France or identified with Mali’s former colonizer. Several, including a minister of defense and an important legislator, had attended military-training school in Russia. They paid attention when Wagner, flush with success in the Central African Republic, made its initial approach.

“Wagner said, ‘There is a military solution to the return of Kidal and the north, and we’ll help you get there,’” Lechner told me. “They were going to go after both the terrorists and Tuareg separatists. That was their major selling point.”

For years, Kidal had served as a sanctuary for both rebel groups. The Malian army had withdrawn in 2014, leaving the insurgents to carry out uprisings and atrocities—among them the kidnapping and murder of two French radio journalists by jihadists, and the execution of six civil servants by Tuareg separatists during an attack on the regional governor’s headquarters. I flew into Kidal on a UN plane a decade ago and was allowed to stay for just 24 hours. I couldn’t leave the UN compound without an escort of two armored personnel carriers full of Togolese peacekeepers.

Early last November, a joint force of Wagner mercenaries and Malian troops approached Kidal from an army base about 60 miles to the south. They deployed armed drones, fought various ragtag rebel units on the outskirts of the town, and then stormed Kidal as the rebels retreated into the desert. Hundreds of jubilant people greeted the Russians. But others were wary.

“The army is moving through the town with white soldiers—we don’t know who they are,” an elderly resident told the Agènce France Presse as Wagner seized the old French fort in mid-November. “People are afraid of them, so there’s nothing left in the town except people like me, who can’t afford to leave.”

The Russians had won the Malian government over not only with the prospect of retaking Kidal but also with the promise of delivering the weapons and other equipment that Mali needed to fight its wars. For instance, Mali wanted to purchase a Spanish-made Airbus to transport troops to bases in jihadist-dominated areas. The Spanish couldn’t sell the Airbus without installing a U.S.-manufactured military transponder, used to relay communications. But the Biden administration, citing the Leahy Law, which prohibits direct military assistance to coup states, blocked the transponder deal and “essentially killed the entire sale,” Peter Pham, the Trump administration’s special envoy to the Sahel and now a distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council, told me. Another obstacle to the transponder sale, according to Corinne Dufka, who covered the Sahel for Human Rights Watch from 2012 to 2022, was the presence of a small number of child soldiers in a progovernment militia. She called the U.S. decision in that regard a victory for “human-rights-based moral diplomacy over realpolitik.” But it was also a tipping point for the Malian government as it decided to embrace the Russians.

According to Pham, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov invited a Malian delegation to Moscow, and “they got transponders and everything else.” France began withdrawing its troops from Mali in February 2022; the last soldier was gone by August. The UN peacekeeping force, whose primary mission was to safeguard the French army, was booted out in December 2023.

Today, just about the only trace of the French presence in Mali is the colonial architecture in riverside towns such as Ségou, once the site of the Festival on the Niger, an annual three-day concert held on a river barge that was canceled in 2015 and has never resumed. Ségou, friends told me, is now a favored R & R spot for Russian paramilitaries, who strut through the streets and gather in bars after carrying out incursions on jihadist-held villages and bush encampments.

For the time being, most Malians appear to welcome the estimated 1,500 to 2,000 Wagner fighters spread across their country. An American friend who has lived in Bamako for decades told me that thanks to the Russians, “we’ve been able to regain our territory and our dignity.” The mercenaries had done “horrible things,” but “war is ugly, and France and the UN were useless. Everybody in Bamako is happy about the situation.”

Lechner recalled a similar response in the Central African Republic. “I went by road through the CAR after the 2021 counteroffensive and listened to people saying that they were really happy with the stability,” he told me. “If you go from not being able to travel to the next village without being robbed and killed to being able to move freely, that’s great.”

But this stability comes at a price. “The Russian counterinsurgency doctrine is brutal,” Lechner added. “The logic is, ‘We create so much pain that it stifles any support for the insurgents, and it ends the conflict.’” According to a U.S. investigator I spoke with, on more than one occasion, the mercenaries entered villages in the Central African Republic and executed 15 to 20 members of the Fulani ethnic group “because two principal armed groups were Fulani.”

Wagner has been even more savage in Mali. One of its first documented atrocities occurred in Moura, near Mopti, over five days in March 2022. According to Dufka, who investigated the case for Human Rights Watch, Wagner soldiers along with the Malian army raided a market and, after a brief firefight, “picked up, tortured, and killed 300 people”—all of them men from the dominant Peul ethnic group, one of the country’s poorest. It was unclear, Dufka said, whether the men were directly involved with the Islamists or whether they’d been rounded up and executed solely because they belonged to an ethnic group that has served as a major source of recruitment. The UN later put the death toll at more than 500.

Wagner “has been effective, if you don’t mind [the fact that they’re] shooting down everyone in sight,” Pham said. “They don’t make the distinctions that Western armies make between combatants and civilians.” According to the U.S. State Department, Wagner soldiers have destroyed villages and murdered civilians in the CAR, “participated in the unlawful execution of people in Mali, raided artisanal gold mines in Sudan, and undermined democratic institutions in every country where they have worked.”

Three weeks after Wagner’s victory in Kidal last November, I received a WhatsApp message from Azima Ag Ali, a guide and translator in Timbuktu, 600 miles across the desert. I had worked with Ag Ali, a member of the ethnic Tuareg minority, for years, most recently in 2013, after the city’s traumatic eight-month occupation by al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb.

Wagner had set up a base in Timbuktu in 2022 to facilitate its war against the jihadists. But when the mercenaries got to town, Ag Ali told me, they also began pursuing Tuaregs suspected of separatist sympathies, carrying out acts of “extortion and murder” against them. Tuareg separatists have been quiet in recent years, holding Kidal but otherwise doing little to provoke the Malian government and military. But their very presence in the country was considered an affront to the military regime. Masked Russian fighters, Ag Ali told me, had just raided a health center in a village called Hassan Dina, 30 miles north of Timbuktu, and decapitated the director. In Timbuktu, they were seizing mobile phones of Tuareg males on the streets and searching their messages for signs of pro-separatist sentiment. If they find anything suspicious, Ag Ali wrote to me, “you will be taken to their base at the airport, and your fate will be uncertain.” Most of his family had fled to a refugee camp in Mauritania, “and I am thinking of joining them,” he wrote. He asked me to send him a few hundred dollars to help him escape. I had no way to verify Ag Ali’s claim about Hassan Dina, but Dufka, who has visited the region frequently, told me that his account of this attack and of the arrests and intimidation of Tuareg men in Timbuktu sounded plausible. A Human Rights Watch report published in March 2024 documented summary executions by Wagner in villages throughout northern and central Mali, including three villages near Timbuktu.

Besides engaging in extrajudicial killings, the Russians have provided an illiberal, antidemocratic model for their African clients to follow. The Malian junta has tightened press censorship and largely sealed itself off from the outside world. Mali was once one of the easiest countries in Africa in which to operate as a foreign correspondent; even after an earlier military coup, in 2012, foreign reporters were generally free to enter the country without being questioned. But these days, I’ve been warned, foreign journalists are likely to be arrested at the airport, jailed, or immediately expelled. Dufka and other observers believe that Russian influence is largely responsible for the crackdown.

And yet, across the Sahel, Wagner’s successes in northern Mali have attracted more interest than its abuses. After refusing to deal with the mercenaries for several years, Burkina Faso, which faces a rising jihadist threat, signed a contract this year with the newly named Africa Corps. One hundred fighters are already in the country; another 200 are expected to arrive soon. Russia’s defense ministry is reportedly negotiating with Niger to send an Africa Corps contingent there. Niger’s military junta, which seized power in July 2023, ordered French forces to leave immediately (the last departed in December), expelled the French ambassador, and threatened to shut down a U.S. drone base near Agadez. The regime accused the Americans—who have nearly 1,000 troops in Niger—of violating the country’s sovereignty. In recent months, according to African political sources, Wagner has been talking with a rebel group in Chad about helping the insurgents dislodge the government led by President Mahamat Idriss Déby.

For Putin, Wagner’s expansion across Africa has provided an opportunity to stick it to his Western foes. “The Russians are good chess players,” Pham said, “and for an investment of next to nothing, they have dealt France a bitter blow and have gotten us distracted to no end.” But David Ottaway, a former Washington Post foreign correspondent and now a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., told me that Russia may come to regret its growing presence in the Sahel. The latest Western-Russian showdown, he said, smacks of the proxy wars that he covered in Ethiopia, Angola, and other Cold War battlegrounds. Those conflicts were destructive but in the end failed to bring either superpower a definitive advantage in the jockeying for geostrategic superiority. He says that beneath public expressions of dismay, U.S. officials may be watching the growing Russian entanglement with equanimity—or even a degree of satisfaction. “Good luck to the Russians,” he told me. “If they want to take on al-Qaeda in Africa, I suspect that’s fine with us.”

After a month-long silence, I asked my former translator, Azima Ag Ali, whether he had decided to flee Timbuktu. He was still there, he answered. The governor had begged the Russian mercenaries “to be more cooperative with the residents,” he texted me, and as a result, “the city is calmer now.” Some of those who had fled to Mauritania had even begun trickling back home. But the Russians still appeared to be operating with impunity in the remote villages of the Sahara, he wrote, and “people are afraid.”