For writers living under an authoritarian regime, the price of intellectual independence is clear—censorship, prison, exile—but so is its value. They are compelled to understand inner freedom as the essential condition for doing their work. Their determination to say what the state doesn’t want to hear gives them a sense of connection with one another, a community of writers, even if it happens underground. But authoritarianism is not just a form of government where leaders jut out their chins, jackbooted police march around with batons, and jails fill up with dissidents. It’s also a habit of mind, marked by impatience with complexity, intolerance of dissent, readiness to coerce agreement. The authoritarian spirit can infect democracies that have long traditions of freedom, but it uses weapons other than state power. The main one is public opinion.

Perversely, the same community that gives writers in repressive regimes the courage to say what the state doesn’t want to hear can, in a free society, become a tool of conformity and social coercion. In some ways, the threat of ostracism from your group is harder to resist than the threat of legal punishment from the state, because it undermines your sense of identity and belonging, your self-worth. Torture and prison are not the only ways to compel people to act against their own values and say what they don’t believe. The pressure to conform and the fear of being cast out have caused an entire political party to prostrate itself before Donald Trump. The authoritarian spirit seems capable of taking root in almost anyone, anywhere—at a MAGA rally, in a college classroom, even among a group of writers.

The organization PEN was founded more than a century ago to provide an international community of support for embattled writers. Today PEN’s American chapter is in crisis, because a group of writers has chosen to turn their community against the organization.

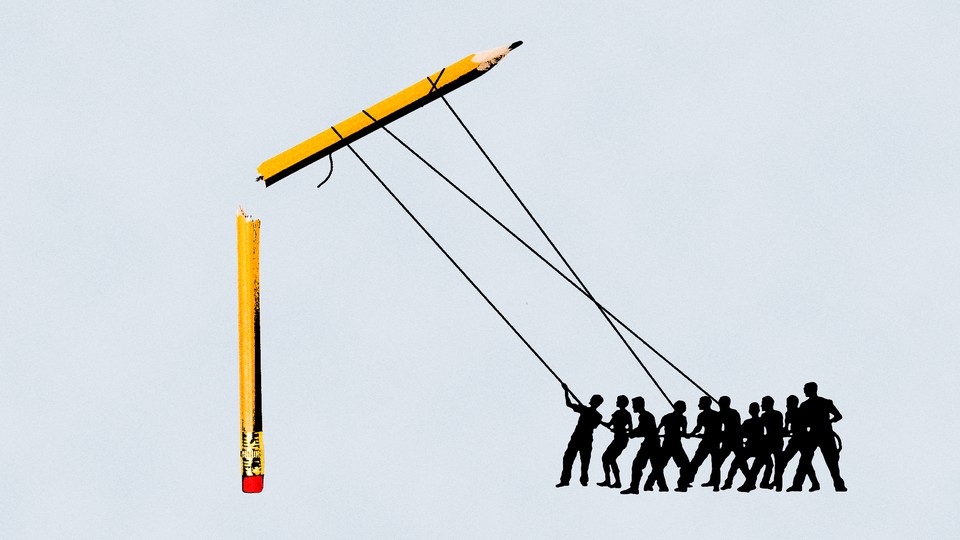

Last week a boycott forced PEN America to cancel its annual World Voices literary festival. The boycott’s leaders included authors of best-selling books and winners of prestigious fellowships and prizes—Naomi Klein, Lorrie Moore, Hari Kunzru, Michelle Alexander, and others. According to someone with intimate knowledge of the boycott, its pressure campaign, carried out strategically through online attacks and direct personal messages, was “merciless.” Invited panelists found themselves threatened with isolation by their colleagues or their communities. Some joined the boycott out of conviction. But others fell in line out of fear of harassment or concern for their careers, or they withdrew from the festival when they saw who else was withdrawing, or they worried about the “optics” of sitting on a depleted panel that lacked the requisite diversity. As the dominoes fell, there were more and more reasons not to be seen standing. After PEN America—on whose board I serve—announced the festival’s cancellation last week, a number of writers privately expressed their unhappiness, but almost nothing was said publicly.

We like to think of writers as courageous individuals who believe in free expression without fetters. In practice, they turn out to be no more able to resist the authoritarian spirit than most other people—maybe less. In the Soviet Union, many writers denounced their imprisoned friends without being told to. Here, they check their social-media traffic first.

The boycott succeeded in silencing 80 writers and artists who were scheduled to speak at the festival and did not join the boycott. They included a few from countries where the cost of free expression is more tangible than social scorn, such as the Uyghur poet Tahir Hamut Izgil, the Indian novelist Geetanjali Shree, the Mexican writer Carmen Boullosa, and five young Afghan women from ArtLords, an international organization of street artists devoted to human rights. After the women fled Afghanistan and became refugees, the Taliban painted over or erased all 2,200 of their murals. Now they’ve been silenced twice—the second time in a democratic country and by their fellow artists.

It isn’t a pretty sight when writers bully other writers into shutting down a celebration of world literature—especially when big names with the most expansive free-speech rights in the world take away a platform from lesser-known writers hoping to reach an audience outside their own repressive countries. Leyla Shukurova, an Azerbaijani German writer who just finished her first story collection and was planning to attend the festival, wrote after the event was canceled to thank PEN for “upholding the values that this festival, as well as PEN America as an organization, represents,” but she added: “The suppression of political discourse that we are witnessing right now in the US is very alarming and unsettling.”

The cancellation of one literary festival by writers—a kind of man-bites-dog story—may seem small, but it is part of a much bigger thing. The cause of the boycott was Gaza. In many ways, it’s a compelling cause. PEN America, like so many other organizations, had fallen into the habit of releasing statements about issues tangential or unrelated to its essential purpose. After October 7, PEN was internally divided over the war between Israel and Hamas, and slow to report on the deaths of scores of Palestinian writers, artists, and journalists. This response was unfavorably compared with PEN America’s vigorous stand for Ukraine after the Russian invasion. When I joined the board at the end of last year, I found an organization under siege from inside and outside. A number of writers and staff members wanted a much stronger response from PEN—not just on behalf of Palestinian writers, but against Israel. They wanted the organization to call for an immediate and permanent cease-fire; they wanted it to denounce Israel’s “genocide.”

These demands were political and geopolitical in a way that diverged from PEN’s charter and mission. They also threatened to tear the institution apart. When PEN balked, the writers found another way to impose their demands. Their boycott, like most protests, soon exceeded its original purpose of stating a position of individual conscience and turned into an organized campaign to shut down the festival, as well as PEN’s literary-awards ceremony. Criticizing PEN and Israel didn’t require silencing writers. Geetanjali Shree, the Indian novelist, wrote me afterward: “I hold strong views against Israel but I believe PEN stands for free dialogue and debate and in unequivocal defence of human rights.” But the writers’ disagreement with PEN had become a quest for power over PEN, even at the price of others’ right to free speech and the organization’s future. The boycott was an expression of the authoritarian spirit.

This turn was perhaps inevitable, because authoritarianism is the spirit of the times, around the world and in this country, where it animates both the right and the left. The two sides have vastly different values and goals, and they use different language—the left’s is academic and specialized (decolonization, imperialism, marginalization) while the right’s is crude and abusive (libtard, groomer, hoax). But in both cases, the words aren’t meant to invite a reply or open a dialogue; they shut discussion down. The two sides reflect and require each other, driving each other to greater extremes, while between them the center of Never Trump conservatives and traditional liberals, with their creaky institutions and halting appeals to reason, collapses.

This is how the authoritarian spirit plays out in a democracy. A party leader compels other politicians to defile their conscience and succumb to his dictates. A political rally turns into a violent effort to overturn an election. A student protest starts with calls for peace and ends in eliminationist chants, vandalism, closed campuses, and an invasion by police or state troopers. A group of writers bring an organization dedicated to their freedom to its knees.