On November 26, 2003, supersonic airplane Concorde made its last flight, returning to the airfield near Bristol, in southwest England, where it’s remained since.

As this marvel of modern engineering soared over the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol, a landmark of Victorian engineering based on a design by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, it created a poignant moment witnessed by cheering crowds.

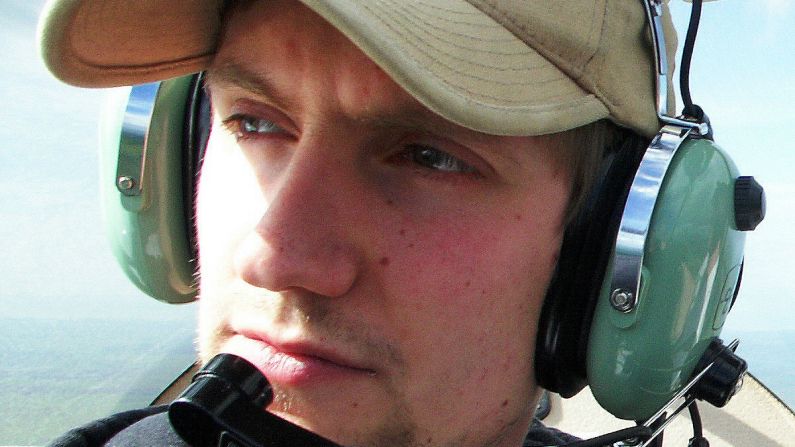

High in the sky, dangling out of a helicopter and buffeted by icy winds, photographer Lewis Whyld managed to capture it on camera – an image that has become the defining shot of the golden age of faster-than-the-speed-of-sound travel.

Whyld, who now works as an aerial cameraman for CNN, reveals how he took one of the coolest airplane photos ever taken.

The photographer’s story

I remember somebody shouting: “There it is, there’s the aircraft!” I was so excited just to see it, I took a picture straight away, and then thought, “hold on, I’ve got to wait until it’s over the bridge.”

We were, I think, at about 3,000 feet, with Concorde 1,500 feet below us. I was standing on the skid outside the helicopter, freezing cold, with downdraft from the rotors blowing on me. I couldn’t feel my fingers, couldn’t feel my toes, couldn’t feel my face.

It wasn’t an easy shot. I had to lean right out of the helicopter because of the angle we were flying at. I was terrified. Terrified of the newness of being in a helicopter for only the second time in my life, terrified of messing the job up.

I was 25. I’d only recently been hired by an agency called South West News Service, which supplies images and reports from the southwest of England to national UK and international media. When the Concorde job came up, I simply put my name down for it.

The only thing my boss really said to me was just, “don’t f*** this up.”

3,000 feet in the air

Because we were in a helicopter, there was a lot to go wrong. Trying to line everything up in three-dimensional space was a challenge. The chances of the plane flying over the bridge at exactly the angle we needed were small.

And, of course, the plane was moving very fast.

Whereas today, you can fire your camera in a burst and get a selection of images, back then they were much slower. I only had one shot.

The plane was so white in the bright sunlight, against a dark background of foliage and the river, the contrast was huge. It would’ve been easy to overexpose Concorde and just be left with a white triangle with no detail.

Because the plane was traveling so quickly and my focus point was so small, it would’ve also been very easy to focus on something on the ground, leaving the Concorde a blurry mess.

And the helicopter was constantly moving. The pilot couldn’t hover, we had to fly in circuits – something to do with keeping the helicopter in the air.

Trying to balance those things out, you stop the aperture down so that you have more depth of field, but that lowers your shutter speed, which means you could get blur if you move the camera too quickly. There was a lot of mental arithmetic and I probably changed my camera’s settings 10 times before Concorde arrived

Capturing the moment

The Concorde experience in photos

There was no trial and error. When the airplane flew by, I would get one chance to take the picture.

And then it was there, banking in the sky beneath me.

I was standing on the helicopter’s skid and leaning out, pulling against the harness, over thin air and shooting the picture, just as it passed the bridge.

I didn’t realize the photograph would make that shape it does – with the cliff face, the bridge and the crowd all kind of framing the aircraft, against a relatively clean background and almost mirroring the shape of the wing.

Everyone loved Concorde, so having that human element in there meant that the picture was elevated a bit more than if it was just empty scenery behind.

Brunel’s Suspension Bridge also helped – the engineering triumphs of the 19th and 20th centuries together.

After the fly-by, we landed at Filton airfield, where Concorde had also landed. I took other photos of the aircraft being towed into its hangar, with the pilot waving from the window.

Then I started to edit my images to send them back to the office.

I remember people looking over my shoulder when I brought the bridge picture up on my laptop. I really didn’t know what I had, right then. I didn’t know that it was a special picture and people would really love it. I was just thinking, “job done.”

Then people started crowding behind me. Other photographers said: “Well, what’s the point in us sending anything, because that’s the one that everyone’s going to use.”

I had no idea at the time that that would turn out to be true. It did run in all the newspapers – of course they used other shots too – but that was certainly the main one.

Some produced it as a collector’s poster. I got my mum to collect the tokens needed to send off for them. Some of the newspapers sent me bottles of champagne. I’d never known anything like it.

Enduring image

The image certainly made an impression with aviation fans.

I’ve been contacted by a few groups asking if I can help get Concorde flying again. Ironically, I thought it would be better for my photo if it didn’t ever take off again, as that would no longer be the last flight.

But it is an incredible machine. I didn’t ever get the chance to fly on it and, in fact, I’ve never actually been on it. I’ve only seen it from the outside, beneath me. That was the first and the last time that I saw it flying.

In the 20 years since 2003, I’ve taken other memorable pictures, but you’re always remembered for your greatest hits and I guess that will always be – in inverted commas – one of my “greatest hits.”

Part of that is because of the picture and part of it is because there was no other chance to do it. So no matter how good the picture is, it would always be the last picture of Concorde. I was lucky that it happened to be a good one.

I’m quite known for doing drone footage now. So, this was my first aerial picture and from then I’ve coincidentally made a bit of a career niche out of taking photos from the air.

Even with advances in technology, if we went back and did that Concorde shot again we’d have to use a helicopter. A drone wouldn’t be permitted to hover over the airplane and take pictures.

So we would still do it the same way, but we’d have better cameras and I would come back with a burst of pictures that we could choose from, rather than just one.

But in some ways, I am quite glad the technology was as it was – because there is just one photo. We’re a bit spoiled now and having more than one version of an image can water down its power.

Changing technology

Interestingly, although camera technology has moved on, aircraft technology, in a lot of ways, hasn’t. Back then you could get to New York in three and a half hours. Sure, we have bigger aircraft – the A380 for example – but in terms of raw speed, Concorde’s still the pinnacle of aviation.

The photo represents the end of an aviation era – and nothing’s come along to replace it, certainly nothing’s grabbed the public’s imagination like Concorde. I think part of the reason the picture still resonates today is due to that enduring affection we all have for that bygone era of travel.

There are always rumors of new supersonic aircraft in the works, and I enjoy tracking the updates, but nothing seems concrete yet. I’d love supersonic travel to come back in a greener, more modern form – to shorten distances across the globe and make the world an easier place to traverse.

Plus, it would just be a mark of human ingenuity to see something like that back in the skies, which would be great from a geeky standpoint. But while I’m keeping an eye out, I’m yet to see anything close to realization.

If I were to take the photo today, I would have also much higher resolution camera, so I would be able to take a wider picture that we could then crop to different compositions. At the time I used a relatively long lens and it’s really the full frame that you see, that is the best way to get the highest resolution possible out of the picture.

Now we could afford to use a wider lens and still get a high-resolution picture if we needed to zoom in afterward, but at that time we didn’t have that.

The general consensus at the time was to shoot the shot on a wide lens, and be as close to the aircraft as you possibly could. But then that would obviously mean the bridge would be tiny in the background, and you wouldn’t get the same kind of effect. I gambled on the long lens and it was only later, as a I gained more experience, that I realized that was a quite a risky thing to do. It means you’re shooting in a narrow space. As it was, everything lined up, everything worked out – but generally speaking those things don’t tend to line up so perfectly.

I was very gung ho and confident back then – knew what I wanted and figured there was no reason why it wouldn’t work out. I guess you get a bit more jaded or realistic as life goes on. But I’d like to think that today I would still take that risk and try and take the ultimate photo, rather than trying to play safe and getting something that people don’t really remember.

Twenty years on, there are postcards of my photograph and posters – there’s even a cross-stitch. In the early years, people would gift me that kind of thing all the time. I think I have at least one jigsaw somewhere in my house. I’ve been approached to do a limited-edition print run.

With modern technology, in terms of editing, we could make a better print of the photo than ever before. We can’t change the camera it was taken on, but we can change the way that we edit it and the details that we draw out.

I still have the digital negatives, so we can always go back to the raw file and take it into the digital darkroom – and then run it through the incredible modern technology that we’ve got today to extract details that we couldn’t previously.

There are methods to increase the resolution, make old photos high quality, get more detail – especially with AI. But I don’t want to change the nature or the reality of the picture. I don’t want to manipulate it any way.

Incredible opportunity

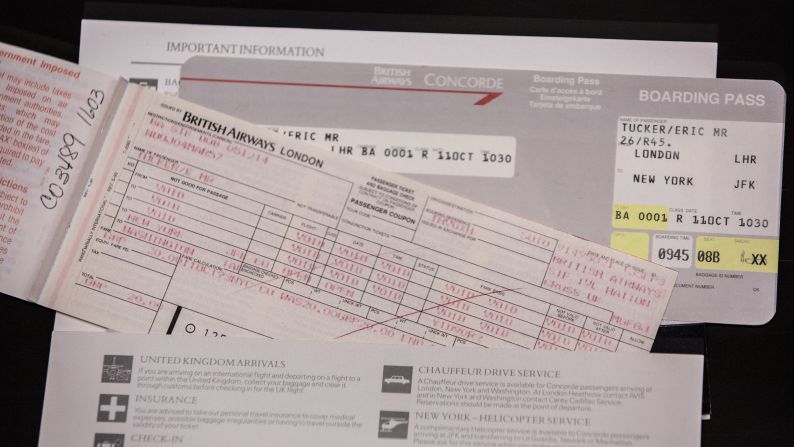

Looking back, I was surprised, actually, that the final flight of Concorde would be this small hop from London to Bristol, but it was a chance for our photo agency to punch above our weight, to compete with international photojournalists from New York and London.

It was a fantastic opportunity to take a great image on a story that wasn’t really political, wasn’t terrible, wasn’t a disaster or anything like that.

In a way, I’m pleased that one of my enduring images is of something that’s celebratory, rather than depressing or a disaster, like all the hurricanes and typhoons I’ve been to, all the war zones and riots. There’s something uplifting about the Concorde photo.

In the years since the final flight, I moved on from Bristol to London. I worked for the UK’s Press Association and The Telegraph newspaper before eventually moving to CNN to shoot aerial footage, videos and drone footage. I was a part of the CNN team covering the Ukraine war which won an Emmy earlier this year.

The Concorde shot was always the springboard for my career. It’s where it kind of all started. After that people knew my pictures and offered me jobs. It oiled the wheels, moving my career forward.

I didn’t expect that to happen when I took the photo, but I’m grateful for it.

This article was originally published on November 26, 2018. It was updated and republished on November 26, 2023.