Were miners' lungs passed on for research without consent?

- Published

During the 1970s, hundreds of deceased miners had their lungs removed and passed on for medical research. Was this done without the consent of miners or their bereaved families?

Black lung disease, formally known as pneumoconiosis, is a horrible condition caused by inhaling coal dust.

"It was really bad," ex-coalminer Michael Quinn recalls, memories flashing of seeing his colleagues left unable to breathe.

His friend and fellow former miner David Cradduck nods in agreement, adding: "It wasn't really talked about, it was worried about.

"Everybody thought 'I don't want to catch that'.

"But it was just looked on as an occupational hazard."

During the 1960s alone, some 16,000 miners were certified as having the condition across Great Britain.

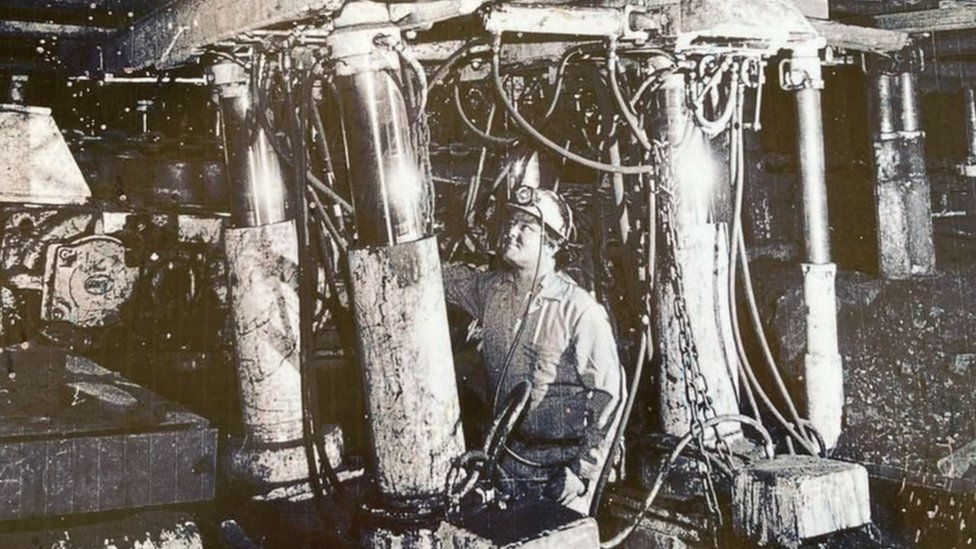

Michael and David, who worked at the Haig Colliery in Whitehaven, Cumbria, know many miners who were struck down by black lung.

In a bid to learn more about the disease, the National Coal Board started a major research project which in part relied upon inspecting the lungs of dead miners.

Chris Fairbairn, who worked in the mortuary of Whitehaven's West Cumberland Hospital, can remember being asked to help preserve organs.

"If [the deceased] was a miner with black lung, we'd take the lungs out and set them up in a preservative," Chris, who now lives in Canada, says.

"I was told that every three or four months, a panel from the National Coal Board would come and do their dissecting and then they'd say 'thank you' and leave," he adds.

Records of post-mortem examinations and inquests from the 1970s show references to lungs and hearts being kept to be examined by so-called Pneumoconiosis Medical Panels (PMPs).

There were nine such panels made up of clerical assistants and medical officers. They were overseen by the then-Department of Health and Social Security (DHSS) to assess miners' conditions and determine their entitlement to pensions and benefits.

When a miner died and it was suspected they had pneumoconiosis, local coroners in England and Wales were required to inform the PMPs when and where a post-mortem examination would be taking place.

At the government's request, thoracic organs such as the lungs and hearts were then made available to the panels for further analysis.

Bruce, who worked as a clerical assistant for a panel in the mid '70s and asked the BBC not to use his surname, remembers lungs and hearts coming into the office.

"They would come in via a courier in a sealed polythene bag," he says, adding they would then be repacked and sent on for further study to hospitals, research departments or the Department of Health.

Such handling of organs was ruled over by the 1961 Human Tissue Act.

Under that act, where a person had not specifically stated their body could be used for research, their bereaved family would have to consent, according to Sir Jonathan Montgomery, Professor of Health Care Law at University College London.

Records at the National Archives in Kew contain letters about the practice, with references to studies by the Institute of Occupational Medicine (IOM) in Edinburgh.

The IOM was set up by the coal board to study lung diseases in miners, with one study published in 1979 based on organs from 500 miners from across England, Scotland and Wales who had taken part in a Pneumoconiosis Field Research (PFR) study.

Most of the organs were supplied by the PMPs, but some also came directly from pathology departments at six hospitals, including West Cumberland.

West Cumberland said it could not provide any information around the study or how consent was gathered, as its records did not go back that far.

The Trusts responsible for the other hospitals, Ballochmyle Hospital in Ayrshire, Sunderland General Hospital, and Burnley General, said similar.

Coventry and Warwickshire Hospital also could not provide further detail, but it was operated by a different trust at that time.

Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust said while it had no knowledge of the studies and involvement of Ashington Hospital, it was aware of and regrets the distress that such historical UK wide research practices have had on relatives of the deceased.

The IOM said it was unable to comment as it did not have the information available due to records being destroyed after 15 years.

Professor Anthony Seaton, who was the IOM's director in the late 1970s, said: "I can't say in individual cases but consent from the relatives was given to allow a post-mortem examination which would, in those days, have implied removal of organs for examination and, if no disapproval had been announced, their use in teaching and research.

"So there was an overall belief at the time that organs removed at autopsy with proper permission could be used."

'Ethical purpose'

Meeting minutes from the IOM also reveal that the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) were approached to help in obtaining lungs, and it agreed.

The NUM said it could not find any specific reference to indicate that the union were aware of or endorsed the sharing of organs for research from coal miners.

What is evident within archive government papers is that concerns were being raised about what the panels were doing with the organs, and how that sat within the law at the time.

In short, was it permissible for the organs to be passed on to groups like the IOM, with the PMPs warned it "should not be done without proper authority in writing"?

Prof Seaton says: "We were completely unaware of any objections to us having the lungs. The panels would just have them incinerated after examining them so it didn't seem unreasonable to use these lungs for the purposes we used them for, for the benefit of miners.

"It was all done for a very good, honest and ethical purpose."

The government did not respond to requests for a record of the historic practices.

Paperwork for the 500 coal miners is scant, so who consented to what remains a mystery.

For the former Whitehaven miners David and Michael and their colleague Tom Scott, questions remain about what the families of their friends knew and agreed to.

"I could understand why they were doing it for research but it didn't filter down to us," Tom says, adding: "I can't see the wives agreeing with it for a start off, if their husbands' parts were sent all over the country."

David agrees, adding: "These hard working people deserve more respect than that."

- Published11 January 2016

- Published29 December 2023

- Published9 October 2017