Scientists have discovered a genetic variant that could reduce the odds of developing Alzheimer's disease by up to 70 percent. By learning more about this protective variant, the researchers hope to open new avenues in Alzheimer's drug development to effectively prevent or treat the disease.

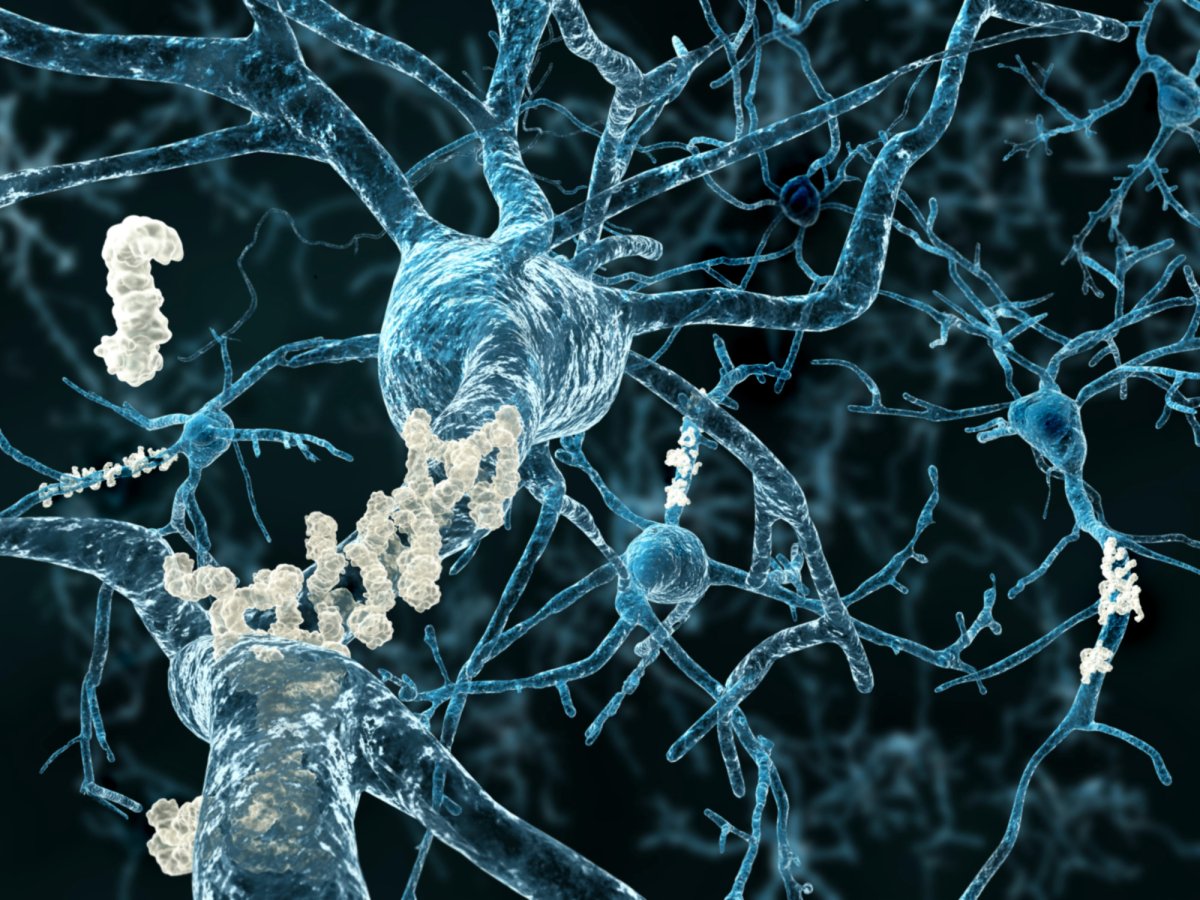

Alzheimer's affects roughly 5.8 million Americans, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The progressive condition is characterized by memory loss and cognitive decline in the brain regions involved in thought, memory and language.

Read more: Compare Top Health Savings Accounts

Scientists believe the condition is caused by an abnormal buildup of proteins in and around the brain cells, but exactly what triggers this process is still unclear.

Certain genetic variants that have been discovered are associated with an increased likelihood of developing the disease. But new research from Columbia University, published in the journal Acta Neuropathologica, suggests there may be other genetic variants that can protect us.

The gene of interest here is involved in the production of fibronectin, an important component of the blood-brain barrier that controls the movement of substances in and out of the brain.

In healthy individuals, fibronectin is usually present in only very small amounts along the blood-brain barrier. However, in people with Alzheimer's this molecule has been detected in much higher quantities.

"It's a classic case of too much of a good thing," said Caghan Kizil, co-leader of the study and professor of neurological sciences at Columbia University's Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, in a statement. "It made us think that excess fibronectin could be preventing the clearance of [abnormal protein clumps] from the brain."

In previous research, the team has shown in animal models that clearing this built-up fibronectin can increase the clearance of abnormal proteins from the brain and improve other signs of damage caused by Alzheimer's. In the latest study, the team demonstrated that a variant of the fibronectin gene appears to prevent this buildup of fibronectin in the blood-brain barrier and thus protects against Alzheimer's, even in those who may be genetically predisposed to the disease.

Previous studies have shown that a variant of the gene APOE—involved in making the proteins that help carry cholesterol and fats through the bloodstream—appears in 40 to 65 percent of Alzheimer's patients. The variant is known as APOEe4, and it is thought to exist in roughly 20 to 30 percent of the U.S. population. However, not everyone with APOEe4 goes on to develop the disease.

"These resilient people can tell us a lot about the disease and what genetic and non-genetic factors might provide protection," study co-leader Badri Vardarajan, an assistant professor of neurological science at Columbia, said in a statement. "We hypothesized that these resilient people may have genetic variants that protect them from APOEe4."

To confirm this hypothesis, the team sequenced the genomes of several hundred people with the APOEe4 variant over the age of 70, including those with and without Alzheimer's. They then shared these results with other researchers at Stanford and Washington universities who replicated the study and came to a similar conclusion.

"They found the same fibronectin variant [was more common in participants who had not developed the disease,] which confirmed our finding and gave us even more confidence in our result," Vardarajan said.

By combining these two datasets, the team found that out of a sample of 11,000 patients, this specific fibronectin variant reduced the odds of developing Alzheimer's in APOEe4 carriers by 71 percent. And it appears to hold off the disease by roughly four years in those who eventually go on to develop Alzheimer's.

From their sample, the researchers estimate that around 1 to 3 percent of APOEe4 carriers in the U.S.—roughly 200,000 to 620,000 people—may also carry this protective genetic variant. This variant likely protects against Alzheimer's in non-APOEe4 carriers too.

"There's a significant difference in fibronectin levels in the blood-brain barrier between cognitively healthy individuals and those with Alzheimer's disease, independent of their APOEe4 status," Kizil said.

But even among those who do not carry this protective variant, the study's findings open up new doors for the discovery of future Alzheimer's treatments.

"Anything that reduces excess fibronectin should provide some protection, and a drug that does this could be a significant step forward in the fight against this debilitating condition," Kizil said. "Our findings suggest that...we may be able to develop new types of therapies that mimic the gene's protective effect to prevent or treat the disease."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Pandora Dewan is a Senior Science Reporter at Newsweek based in London, UK. Her focus is reporting on science, health ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.