When the British journalist Don Iddon boarded the S.S. United States in 1954, his first act was to locate a copy of the boat’s first-class passenger list. As he read it, his heart sank—sure, Harry Truman’s daughter, Margaret Truman, was on board, and so were a few prominent businesspeople. But the list, as he wrote later and Steven Ujifusa recounts in the book A Man and His Ship: America’s Greatest Naval Architect and His Quest to Build the S.S. United States, contained a distinct lack of “big names.”* Where were all the movie stars?

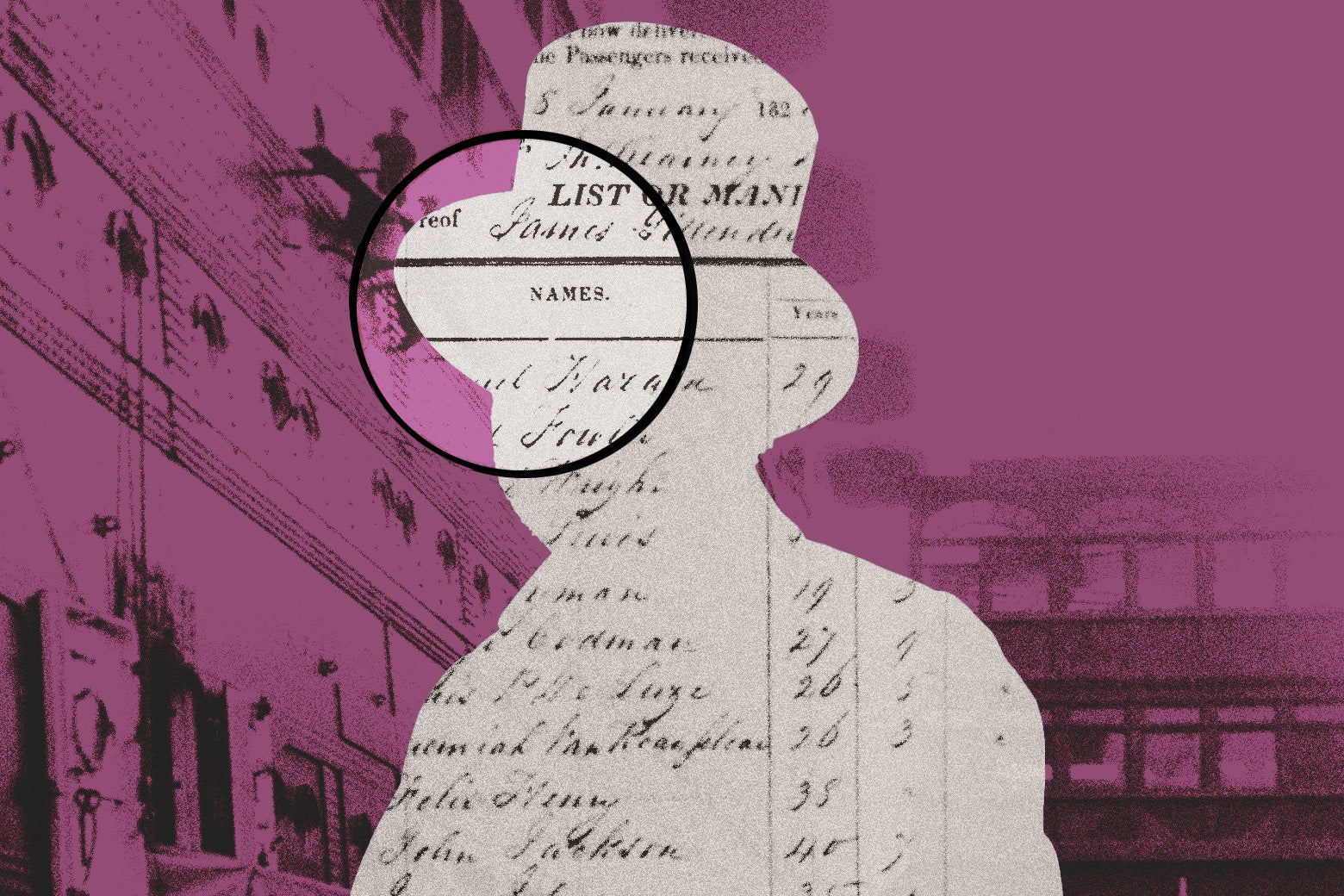

With the rise of steamship travel in the 19th century and into the 20th century, passenger lists were a central feature of any long voyage—a prized preview among passengers of the kinds of people with whom they’d be rubbing shoulders throughout their journey. Lorraine Coons, a historian who wrote a book on steamship travel, told me that in her research she first notices them popping up around the 1880s. These lists, often color-coded by cabin class, were handed out to new arrivals, who invariably scoured them for names of celebrities. It didn’t matter whether your reputation was favorable or in disgrace—anyone with a high profile would make for good entertainment during the voyage. Journalists obtained copies too: When ships departed from port cities, local reporters ran articles listing out all of the most famous names on board.

What made these lists so unique is the sheer transparency they offered. Royals, politicians, and A-list celebrities were named alongside regular midtier passengers, a rare blending of social classes that, in 1910, prompted one writer to bemoan, “The very best people are set down cheek-by-jowl with the nobodies.” But that accessibility was also the beauty of the passenger list. There was no loophole for the richest travelers: If you wanted to ride on the boat, you had to be on the passenger list.

Today we no longer really have a comparison—those cryptic, initialed upgrade monitors at the terminal gate don’t quite scratch the same itch. On airplanes, travelers are reduced to shuffling through first class while trying to surreptitiously spot a famous face. Increasingly, even that has become difficult, as celebrities flee to full-scale private suites and terminals before boarding their flights via VIP programs that whisk them to and from the plane. For the truly intrepid, there is one way to track a celebrity’s travel movements, through publicly available private jet flight data—and the likes of Taylor Swift and Elon Musk have attempted to quash it.

Although a return to the officially sanctioned nosiness of the steamship era is unlikely, in today’s hyperstratified world, where the wealthiest can pay for the privilege of privacy, we could probably use a little bit of that social transparency. Those old passenger lists helped puncture, at least briefly, the classed dynamics of travel—offering everyone on board equal access to gossip. There was no harm in a little bit of intrigue about your fellow passengers. And who knows: Maybe getting our hands on a list of names could make an international flight a bit more bearable today. A little speculation about the other high-powered travelers on board could ease the tension at high altitudes, inside what is historically a pressure cooker of resentment.

In the context of a weekslong steamship voyage, it was perhaps inevitable that passenger lists would become objects of careful study. In the early 20th century, the glamour of an international voyage got travelers only so far. Once passengers were away from shore, one of their great challenges was to stave off boredom. Some ships offered lectures; others engineered musical bands out of ship staff; the Île de France had a bowling alley. What activities the vessels didn’t offer, passengers often cobbled together for themselves. Steamship travelers organized theater programs, boxing tournaments, or large balls. At night, they blasted dance music from gramophones.

And so gossip became a commodity. Many passengers took to self-publishing their own steamship newspapers, covering the personal histories of those on board. Some ship newspapers published blind items about passengers. The historian Martyn Lyons discovered that in the margins of one surviving copy of the Tamar Times, a reader had hazarded guesses about which traveler each blind item referred to. Analyses of passenger lists often appeared in these newspapers too. On one ship, a passenger published a single-issue newspaper called The Rolly-Poly, which included an analysis of all the passengers on the list: “Of the women, all are wives except 78 who aspire to be.” Even the elite consulted these lists to choreograph their social interactions, lest they accidentally get stuck in a conversation with someone unrefined.

That the lowly passenger list could become a focal point speaks to just how dull these journeys were. Passenger lists were not Wikipedia entries: They were bare-bones documents, generally offering names and nothing more. A few steamship operators, Coons told me, did also list travelers’ place of residence, but most were strictly limited to names. Passengers were forced to spin out the (perhaps embellished) backstories of the celebrities on board by pooling together their own spotty memories.

Despite these limitations, observers found ways to sleuth out the rich and famous. A name preceded by a title like “Baroness” signaled a person of importance, and so would the size of each passenger’s entourage. It wouldn’t be uncommon for a rich person’s name to be listed alongside “two nurses and a governess.” One passenger list, for instance, noted the presence of “J.K. Smith and valet.” The medical professor William Thomas Corlett recounted the feeling of disappointment in the quality of the guests on board a ship he rode—that is, until he consulted the list. Only then did he note with pleasure the presence of “Herr von This and Herr von That,” as he put it, “together with a sprinkling of Barons and a Baroness or two.”

Not every steamship company loved the passenger list. Some devised ways to keep their steamships as exclusive as possible so that passenger details wouldn’t spread to the public. The S.S. Carolina, for instance, did not let passengers book partial journeys, for fear it would bring in middle-class clientele and lead to leaks of the passenger lists. Basically: You had to afford the whole trip, or you couldn’t board.

Yet the passenger lists that did reach the public have, in recent decades, taken on an outsized importance. Genealogists and historians alike now rely on passenger lists to track how people moved across the world. Amateur genealogists on Ancestry.com regularly take advantage of passenger lists to trace their roots. So does our most famous chronicler of family history, Henry Louis Gates Jr. In retrospect, these documents also charted social transformations: It wasn’t uncommon for immigrants to include a new name when boarding a steamship, or for trans passengers to embrace their preferred gender. I thought a lot about passenger lists while researching Zdeněk Koubek, a high-profile Czech athlete who transitioned gender in 1935, for my forthcoming history book The Other Olympians. In 1936, when Koubek was newly living as a man, he visited New York, and he appeared in the passenger list alongside his new gender: “Mr.”

I’ll allow that passenger lists may no longer make sense in our tech-surveillance world, where even a simple series of names would get scraped by algorithms. But I think we’ve lost some sense of camaraderie without them—lost that thrill of unfurling the manifest and wondering what you might find. These lists could impress, or they could disappoint, but they always entertained. In 1901 Mary Lawrence, a wealthy Bostonian, leafed through the first-class passenger list of the steamship Oceanic. She was excited to see the name of Otho Cushing, an illustrator and cartoonist whose work she knew. “Here at last was one interesting fellow traveler,” she wrote in her diary, according to the book Seductive Journey: American Tourists in France From Jefferson to the Jazz Age.

Nearly a decade later, however, when she rode the same steamship again, the list was not so colorful. Lawrence was crushed. “There was not a soul on the passenger list that we had ever heard of before,” she complained. Today Lawrence’s certainty that the list was a complete account of the passengers on board is striking. It didn’t seem to occur to her that there could be loopholes for people who could pay, that you could scrub your name from the manifest if you were famous enough. And perhaps those loopholes really didn’t exist. Steamships had classed cabins, sure, but there was no special treatment for celebrities: At sea, everyone was on the list.

Correction, April 24, 2024: This article originally misidentified the book containing Iddon’s notes on his journey aboard the S.S. United States.