With his new book, Woody Holton shows the US at its founding much as it is today. Then, as now, it was stratified by class and riven by race, religion and gender.

Marshaling a prodigious amount of scholarship, the University of North Carolina professor and Bancroft prize winner challenges much of what we once imagined we knew.

A privileged few conceived and advanced the break with Britain. But because both sides promised freedom and land to Black people and Native Americans willing to fight on their behalf, the marginalized came to see revolt as a golden opportunity too.

Pursuing the promises implicit in the declaration of independence and Bill of Rights, even some women, unmentioned in either document, joined the poor, slaves and Native Americans in alliance with disgruntled white colonists. With much to gain, they resolved to forge a new nation that would put an end to indignities and abuses long endured.

Unfortunately, this was at odds with the aims of the American elite. Notwithstanding all the Enlightenment-inspired sentiments they expressed, a large measure of their intent on gaining independence was to appropriate still more Native land while expanding Black bondage, all to grow ever richer.

Holton shows how the American revolution evolved out of the Seven Years war in Europe, in part pursued in North America as the French and Indian war. “No taxation without parliamentary representation!” So protested American rebels even more provoked by Britain’s imposition of a monopoly on trade. “How else,” the motherland countered, “are the Crown’s expenses, incurred defending our colonial frontier from Indian attacks, to be paid?”

It is remarkable that American colonists took on the world’s mightiest naval power – and won. At the Battle of Long Island in August 1776, 25,000 redcoats faced 9,000 soldiers of the Continental Army. British leaders, however, recognized that fighting in unfamiliar surroundings was hazardous.

Another British advantage raises another issue which confronts us today. As Britain was far more densely populated than the 13 colonies, a much larger number of her fighting force had contracted smallpox already, gaining lifetime immunity. As the disease raged throughout the war, George Washington was left in a quandary.

“During the British occupation of Boston,” Holton informs us, “Gen Howe responded to a smallpox outbreak by inoculating every soldier who had never had it.” Inoculation was the cause of Washington’s worry. An injection of the actual virus, as opposed to vaccination with cowpox, inoculation left patients recovering for as long as a month. Mass inoculation would have incapacitated Washington’s force. But gradual inoculation, a unit at a time, ran the risk of untreated men being infected by those just treated. Worse still, sick soldiers might contaminate civilians.

Holton expounds at length about the double game both sides played against Black people and Native Americans. Beguiled into service with promises of treaties, land, bounties and freedom, both groups were double-crossed again and again. White Americans, from Washington to the pioneer farmers, knew it was wrong to enslave Africans and to dispossess tribes of land and life. Why then did they do it? Neither Christianity nor philosophy could dissuade them from maintaining the privilege and power of wealth. Again, Holton’s book echoes to our own time, when billionaires eschew progressive tax rates and the masses lose income and purchasing power.

Holton’s American founding is flawed by venality but, paradoxically, made more robust by diversity and, ultimately, redeemed and made “more perfect” through atonement for slavery’s original sin.

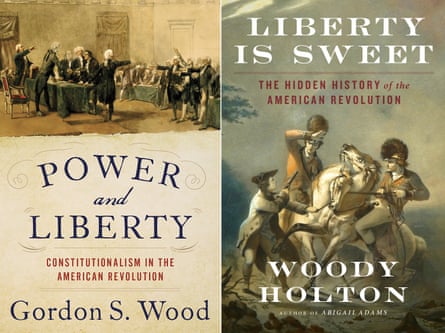

This is at odds with a rival scholar of the American revolution, Gordon Wood. His America dawned pristine, like Venus from the sea. Slavery, antisemitism, misogyny, Native American massacres? What are these among so abundant a fount of freedom? When the two men met recently, to debate, sparks flew. Holton fared better.

Illustrative of e pluribus unum, his new book shows the US has always been a richly complex, multifaceted nation. Though he includes so many hitherto unheard voices, he has hardly included all who were there. Naturally, we read of Abigail Adams and well-to-do white widows dreaming of the vote. We read of Margaret Corbin, a wife who went with her husband to battle at Fort Washington in upper Manhattan, and who after he was fatally wounded manned his cannon, and who was voted a veteran’s pension by Congress. Mary Murray also makes an appearance. She is supposed to have contributed before the Battle of Harlem Heights, offering British officers refreshments of cake and wine and thus delaying the redcoats’ advance.

But where is Miss Lawrence? Hannah Lawrence was a determined patriot and propagandist, ignoring the danger of imprisonment or worse. A Quaker in Manhattan, she wrote and distributed rhyming denunciations of the British occupiers. Her modus operandi was to saunter down to the Battery, where soldiers promenaded, and allow her missives to slip to the pavement before hurrying away. For all her patriotic zeal, though, she found herself defenseless when the authorities billeted Jacob Schieffelin, an officer of German descent, in her father’s house. They married.

Where too is Haym Salomon, a Polish-born Jewish financier? At a critical moment, he underwrote the Americans. His efforts were subordinate to those of English-born Robert Morris, along with Alexander Hamilton and Albert Gallatin credited as a key founder of the US financial system. But Salomon’s work, and that of other Jews, was of enormous importance too.

These are quibbles. Thanks to Woody Holton’s work, now better than ever we are made aware it is not just a small cadre of rich white men who deserve recognition as American founders. Apprised of the true scope and scale of all those involved in our country’s birth, we can celebrate founding mothers, brothers and sisters too. Like us, they were multiracial and of every class.

Liberty is Sweet: The Hidden History of the American Revolution is published in the US by Simon & Schuster