In recent decades New York City has changed dramatically, transforming from the lows of the crime and drug epidemics that ravaged the city in the 1970s and 80s to the resurgence and optimism that typified the 90s and the surge in gentrification that has been a source of debate more recently. Amid all of this transformation, one might make the assumption that these are new forces that New Yorkers are being forced to grapple with – not necessarily so.

In fact, one of the points of the New-York Historical Society’s fascinating new exhibit, Lost New York, is that these forces have been transforming the city for a much longer time. The exhibit brings to light layers of history that have generally been forgotten, showing how landmarks, practices and communities have been integral to the city’s formation, even though they may not be remembered.

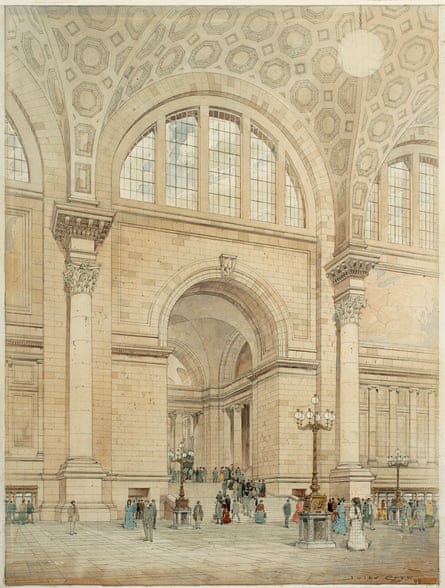

Comprising nearly 100 historical pieces, the show is situated around dozens of landmarks that once defined life in the Big Apple but have since been lost. The offerings range from packs of trash-eating pigs that once roamed the streets of New York to the high-wheel bicycles that proliferated throughout Central Park and elsewhere in the late 19th century to the massive Beaux-Arts Penn Station, once a wondrous site of entry to the city. Throughout the exhibit, quotes from “community voices” – including experts, artists, athletes, self-described raconteurs and even a Yankees fan – add depth and nuance to the history presented here.

According to the show curator, Wendy Nālani E Ikemoto, Lost New York speaks to the importance and impact of preserving what has been lost in memories. She framed the show as not just about disappearance but also about recovery and finding resonance with the contemporary city. To that end, the show deeply ponders questions about how the phenomena that drove historical erasure can be seen in New York’s ongoing transformations, and which contemporary sites might now be implicated by issues like gentrification, class warfare and the need for preservation. “The past only has meaning in relationship to today,” Ikemoto said in an interview. “We want audiences to come away with deep questions into the drivers and consequences of change through the many layers of the city’s past.”

One of the intriguing offerings from this show is the unassuming oil painting No 7 1/2 Bowery, a streetscape of a business building that was made by Prelette Wriley in the mid-19th century. Although audiences might be drawn to take in the Wriley building, horse-drawn carriages, and men and women in period dress that stand front and center in the painting, there is a small detail that is actually most important: the placard for this piece instructs viewers to “note the pig in the foreground”, and the community voice note by the butcher Jennifer Prezioso informs us that at the time “there was one pig for every five people in Manhattan”.

Indeed, at the time pigs were considered an important part of garbage-management in the city, as well as providing an important resource to help lower-income New Yorkers maintain food security. According to Ikemoto, the pigs came when the city was being settled, reaching their height in the 1820s, when about 20,000 pigs roamed the streets. Although the pigs had benefits, they were also considered a menace, tearing up the cobblestone roads, smelling badly, and blocking carriage traffic – no less than Charles Dickens noted the ways in which their presence affected urban life – and eventually they were lost to the tides of history.

According to Ikemoto, the pigs are “a perfect example of resonance with present-day New York”. As the pigs were excluded from segments of the city, the working class moved with them, property values grew, and gentrification took place. Ikemoto sees similar processes working today, just not necessarily with trash-eating pigs. “The presence of the pigs basically created class warfare,” said Ikemoto. “As the pigs were removed, businesses moved in, lower-class New Yorkers moved out, and this is the process that we know today as gentrification.”

As the pigs demonstrate, Lost New York does a great job of integrating multiple communities in fascinating and delightful ways, including the Chinese community, LGBTQ+ individuals, the Black community’s civil rights struggle, and others, as well as bringing in diverse neighborhoods. The omnibus, which was a relatively egalitarian means open to most (if not all) New Yorkers, is a thread running through the exhibition, bringing some cohesion to the many various sectors that are present here. Walt Whitman was a fan, often falling into delightful conversation with the bus drivers, which fed into the creation of Leaves of Grass.

One major landmark that is celebrated in Lost New York is old Pennsylvania Station, which was demolished between 1963 and 1966, and whose elimination was the source of much outrage among New Yorkers. The exhibition features architectural presentation drawings, granting a view of the old station’s interiors, as well as a black-and-white photograph of the demolition. Ikemoto stressed just what a grand, historic landmark the station once was, quoting the architectural historian Vincent Scully, who memorably said of the old station and its replacement: “One entered the city like a god. One scuttles in now like a rat.”

The demolition of the station was important in that it spurred the creation of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. As Ikemoto shared, this was an important step, as she views landmarks as essential to the community vibrancy of a place, and their preservation a valuable part of maintaining a place’s identity and sense of history. “Landmarks are centers for community,” she told me. “They’re places that people can convene around – you can say to someone, meet at the blank. They also become places to help to identify a city.”

To that point, Lost New York isn’t just about commemorating places past but also about realizing the importance of the landmarks that currently exist and the reasons for celebrating and preserving them. Ikemoto hopes that visitors come away with fresh eyes that are more activated to the landmarks that are both gone and still present. “I want visitors to enjoy the exhibition and to enjoy delving into the many deep layers of the city’s past,” she said. “I also want them to come away with critical questions into the drivers and consequences of this loss.”

Lost New York is on display at the New-York Historical Society until 29 September

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion