What marriage means to these same-sex couples

Twenty years ago, same-sex couples walked into city and town halls, synagogues and banquet halls across Massachusetts.

They were there to get married.

On May 17, 2004, Massachusetts towns and cities began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples after the state made history as the first in the country to allow same-sex marriages.

Couples cascaded into clerks offices to make their mark on history. Tanya McCloskey and Marcia Kadish were first in Cambridge to legally marry; they obtained their marriage license minutes after midnight at city hall and were wed later that morning. At Boston City Hall, the couple who became the face of the fight for marriage equality, Julie and Hillary Goodridge, married.

Since that day, well over 30,000 LGBTQ couples have gotten married, according to available state data.

WBUR spoke with four couples who have exercised their right to marry at different points over the last two decades. They shared the experiences that led them to each other and what marriage has meant in their lives.

Gaby Leal and Chelsea Wood

Sept. 12, 2020

“She was my one and only right swipe Tinder date,” Gaby Leal, 35, said.

“She was not my first right swipe, but certainly the best right swipe,” Chelsea Wood, 37, replied. “The last, for sure.”

It was 2016 and Wood was working in San Francisco. Leal, who is from Mexico, was in town for a two-week training.

Leal knew right away Wood was it for her. They dated long distance, flying to see each other once a month, and soon after decided to move to Massachusetts to be together full time.

When the pandemic struck in 2020, marriage became a bigger topic of conversation.

“I started going back to work,” Leal said. She’s a field service engineer who works in hospitals. “It was scary; if anything were to happen, I want you to have rights. I will want people to know that you have a say on my life.”

So in May 2020, Leal bought a ring online and popped the question.

When they told friends and family, the first question was: How are you going to do it?

COVID was not getting better, so they had the ceremony in September in their backyard and invited guests on Zoom.

The only mishap was that Leal forgot to unlock the phone rotation, “so the whole wedding was sideways.”

At the end, everyone offered a toast.

“It took like an hour and a half to get through all the toasts,” Wood said. “And two bottles of champagne,” Leal said.

They eventually celebrated in person, between COVID variants, with a reception at La Brasa in Somerville.

“I wanted to have a Mexican wedding in Somerville, and we accomplished it,” Leal said proudly.

They both donned white dresses, did their hair and makeup, wore heels — and switched to personalized Converses later in the evening (that’s more Leal’s pace). There was a dance floor, a Mexican DJ, and cheese flown in from Oaxaca. Everyone gave speeches and danced.

The couple’s first dance was to a mash up of two songs: Taylor Swift’s “Lover” for Leal, and St. Motel’s “My Type” for Wood.

“So all the traditional stuff," Wood described. "You know, for a very untraditional couple."

The couple has been together for eight years, and married for four. They’ve settled down in Danvers.

Leal said that when she lived in Mexico, it wasn't legal to get married. (The country legalized same-sex marriage in all states by 2022.)

“I never thought that I was going to be able to get married,” she said, “but I always wanted it because I saw my parents and I saw my brother and it just felt bad not being able to have that just because I loved women.”

The couple feels safe living in Massachusetts — with its progressive record on social issues — but Wood said she’s worried the conservative Supreme Court might put the right to marry on the table again.

“I don't feel comfortable about it,” she said. “If Trump gets reelected, I think it's almost for sure going to happen.”

The couple is particularly worried about Leal’s ability to stay in the U.S. She's a resident, but has not been naturalized as a citizen.

“My green card is through marriage and if my marriage is not valid and then what happens to my green card?” Leal said. “So that is a scary part.”

Leal plans to file her paperwork as soon as she’s able.

“A lot of people feel like marriage is just a piece of paper,” Leal said, “but for me, that piece of paper, like makes us together, gives you rights.”

To Leal, marriage also means “I vow to love you until my heart stops beating. It's just a beautiful vow that we do. And I love that.”

Corey Yarbrough and Quincy J. Roberts Sr.

Oct. 1, 2016

For their first date, Corey Yarbrough asked Quincy J. Roberts to the Cheesecake Factory, in Boston’s Prudential Center.

“It was our first, second, third and fourth date,” Yarbrough, 38, remembered, laughing.

That first date was 16 years ago, and the couple is now happily married and settled in Dorchester with their son. “So maybe Cheesecake Factory should be everyone’s first date,” Roberts, 42, said.

Roberts is the visionary one — he’s opinionated and creative. Yarbrough is the strategist, who helps take out of the box ideas and make them happen — he’s compassionate and humble.

Roberts used to wish he was more like Yarbrough, “but as I grow older, I'm like, I don't wish I had anything but what I have. But I admire [him more].”

Yarbrough is the executive director of 826 Boston, and Roberts is the director of special events for the state’s travel and tourism department.

When they started dating, they connected over growing up in the South and learning to find their way in Boston.

“A lot of those early conversations were about trying to survive in Boston as a Black gay man, and that being very, very difficult for us in terms of being able to find community, in terms of being able to find support systems,” Yarbrough said.

Those discussions led the couple to create the Hispanic Black Gay Coalition, an LGBT organization, in 2009 utilizing Yarbrough’s background in community organizing and Roberts’ political fundraising. The organization became the root of their long relationship.

“At that time in my life, marriage didn't seem possible. … I've always struggled with my sexuality, just being from the South, the way I was raised. So, I was one of those people, once I came out, I thought I was going to be one of those uncles that, you know, had the special friend — when we visit on Thanksgiving, that's the roommate or something,” Roberts said.

Yarbrough said he did try to create a future for himself as a married man. Looking back, he feels that part of the reason he moved to Boston was to get space from his family and other things that would discourage him from being his true self.

Part of Yarbrough’s dream was getting married in his church. The couple are members of Union United Methodist Church — one of the oldest historically Black churches in Boston. But when the couple was ready to make their vows in 2016, the church had never held a same-sex wedding ceremony before.

The church trustees had to vote if the couple could get married there because it was against the Methodist faith. Everyone except one person voted in favor of the change.

“I always thought that was funny that these individuals get to dictate whether Corey and I could get married in a building that we work in,” Roberts said. “Like, we really worked there. His office was there. I'm doing youth services there.”

Even as their church in Boston came to allow them to be married in a religious ceremony, they didn’t have a lot of family support. Yarbrough said his mother was his only family member to attend.

“That's bittersweet to reflect on, but I think it is a testament to the love community that we had created here in Boston and that support that we were looking for was still there for us on that big day.”

Roberts’ mom was not supportive at first, but did accept the couple a few years before the end of her life.

“I think that was the half of me that wanted to get married in a church just to show her that I'm still a part of the church, I'm doing amazing things, I'm just your gay son.”

Roberts said they wanted to go through that so other people wouldn’t have to.

They became the first, but not the last, LGBTQ couple to be married at Union.

“I'm not humble about being the first," Roberts said. "It was a vision, like, we're going to be the first to be married in this church, and then we're going to open up the door for everybody else.”

The two wore matching suits — silver, purple and white. But Roberts wore a tie and Yarbrough wore a bow tie, “which is kind of opposite of who we are, because I'm usually the bow tie,” Roberts said, “and he's the tie guy.”

They walked down the aisle to different songs — Roberts to Whitney Houston’s “I Have Nothing,” and Yarbrough to Craig David’s “You Don’t Miss Your Water (‘Til the Well Runs Dry).”

Yarbrough said he was so emotional that he barely got through his vows. “It was just a joyous occasion with the people who wanted to be there, loving on us.”

“Marriage should represent different things to different couples,” Yarbrough said. “I think it's about our bond, our union, our goals and where we want to be five years from now, 10 years from now, and the legacy we want to leave on this earth together and what we support each other to do separately.”

And for Roberts, he said it also shows other gay Black men that there’s hope.

“Young Black boys, whether they're from the South or from Dorchester, Roxbury, they could see someone like Corey and [me]. I say ‘my husband’ a lot and young folks are like, 'You're married to a man?' So it's a conversation starter. It's hope.”

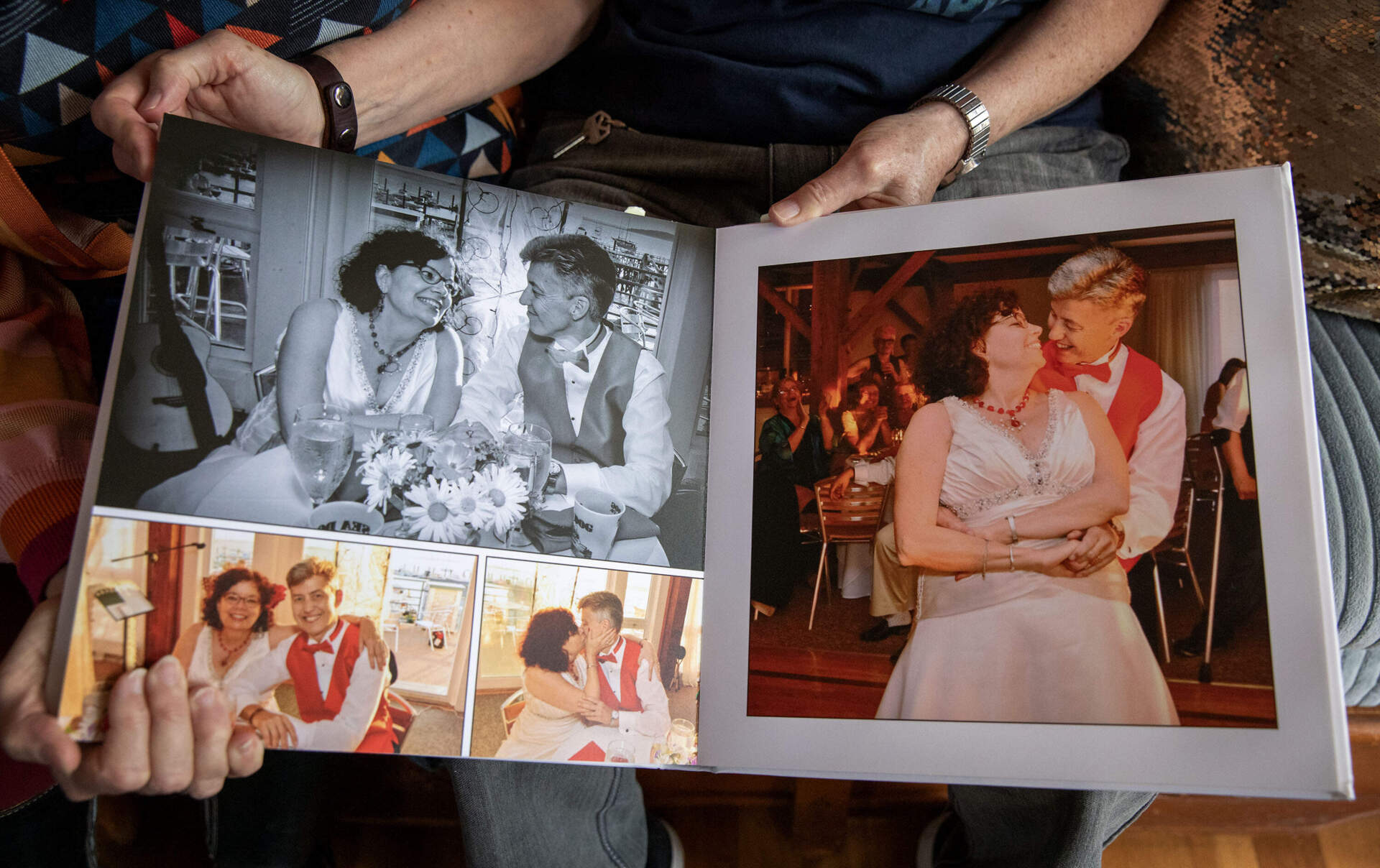

Sandy Bailey and Liz Nania

July 12, 2014

Sandy Bailey, 69, and Liz Nania, 65, met in the basement of the Roslindale house they currently share.

Nania lived there, and had long hosted dance classes in her basement studio.

"I signed up for a dance class and I didn't know that it was going to be in someone's house," Bailey remembered. "A studio in someone's house — an actual dance studio in someone's house," Nania said, correcting her.

This was in 2012; Bailey had lost her first wife to cancer a few years prior. Her friends had been pushing her to go out and do something, and she had always wanted to take a dance class, so there she was.

"I just was taken with her right away," Bailey said. "She called my name, you know, calling a roll call, and when I said 'here' ... wow."

They later learned that they both wrote in their diaries that night about each other.

"I was like, well, there's still smart, handsome butch lesbians out there to be found once I saw her," Nania said. "So it's like, OK, there's hope for me."

"In truth, I took one look at Liz and knew she was for me," Bailey said. "Luckily there were six nights of classes, so I got to dance with Liz multiple times. I wound up staying there a little bit late one night, and asked her out."

Nania said she was drawn to how social, smart, funny and thoughtful Bailey is. And Bailey was blown away by the fun and supportive queer dance scene Nania fostered.

"I knew on our first date that I would marry Sandy," Nania said, which was out of character for her, having never wanted to be married. "But it's like wow, this is the one."

They got engaged three months later, but kept it secret for a while, "cause we knew our friends would freak," Nania said.

They didn't know it at the time, but both of them had been at rallies advocating for the right to marry in the early 2000s at the State House. They weren't part of the "movers or shakers," Bailey said, but "we were both called to be there to push it over the finish line."

Nania had been dating someone around 2004, but it wasn't serious.

"I didn't want to marry her or anyone," she said. "I was really not into being married at all, but I felt like this is a right we deserve."

Bailey also didn't want to be married at that time, but it still felt monumental to her.

"When it passed, I suddenly realized how much it meant — to be considered a full human, that's how it felt," Bailey said. "It felt like the stigma and the eyes that everybody looked at me through had been different ... like you're just so different in that basic human way of wanting to connect with someone, wanting to make them your person, wanting to make a home and a family, all that stuff that is so core to being alive."

"When it passed, I suddenly realized how much it meant — to be considered a full human, that's how it felt."

Sandy Bailey

"It was so electric when it happened. I remember my friend calling me and telling me," Nania said. "I just walked out the door that day, feeling like no longer a second class citizen. ... I just felt 10 feet tall. Like, I'm a real person."

About a decade later, they found each other, and wanted to exercise their right to marry.

When it came time to pick a song to have their first dance to, Nania made a playlist of 20 songs. The couple would dance to them in their home studio every night.

"We danced through them all and just kept crossing them off the list until we were down to two," Nania said. "We picked the one that was the most fun to dance to. It was a very smooth casual dance, no choreography."

It was "Love is Here to Stay," recorded by Ella Fitzgerald.

On the second anniversary of their first date, they got married in a big ceremony at a marina in Hull.

At the ceremony, they read the quote by Justice Margaret Marshall from the state's high court decision that cleared the way for same-sex marriage:

Marriage ... bestows enormous private and social advantages on those who choose to marry. Civil marriage is at once a deeply personal commitment to another human being and a highly public celebration of the ideals of mutuality, companionship, intimacy, fidelity, and family. ... Because it fulfils yearnings for security, safe haven, and connection that express our common humanity, civil marriage is an esteemed institution, and the decision whether and whom to marry is among life’s momentous acts of self-definition.

"We wanted to make it a celebration of joy, and protection for us as a couple, and we sure did," Nania said.

"We were just beaming, like our faces are going to come off," Bailey said.

They had an all-woman swing band, called The Mood Swings, and a DJ. A hundred friends joined. Nania's mom came to the wedding, but otherwise the couple didn't invite family.

"I had not been welcome in my parents home for being a lesbian since my 20s," Nania said.

"Coming out of a lot of gay-related trauma — both of us ... just the magnitude of having a hundred people — a hundred friends, a few family members, a whole orchestra and all the people who worked at the place — stand up and just cheering and grinning their faces off for us," Bailey said.

"I can't imagine what could have healed us as quickly and beautifully as that."

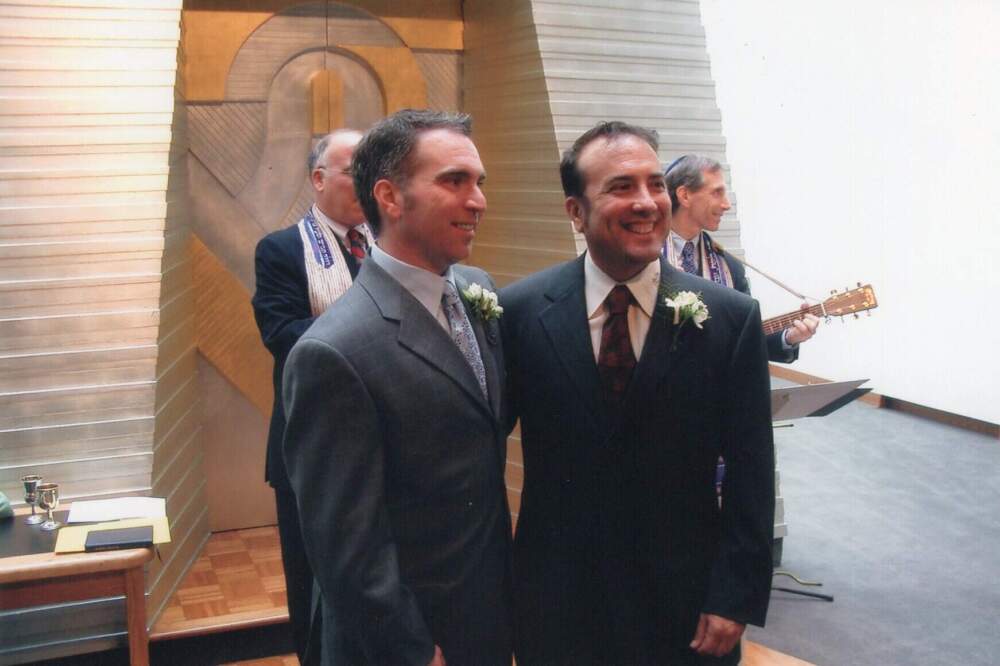

Russ López and Andrew Sherman

May 21, 2004

It was 1984. Graduate student Andrew Sherman introduced himself to his classmate Russ López at the Harvard Kennedy School.

“We had one date and it was terrible. They carded me, and wouldn’t serve me alcohol,” López, who is now 66, remembered. “It was just this madness so we decided to never have another date.”

“We'd just hang out together,” said Sherman, 61.

They didn’t really plan on being together — “at least for the first week or two,” said López. Soon enough, though, López and Sherman never wanted to spend time apart.

The two started a life together and settled down in the Boston area. In those days, the couple said they felt Massachusetts was more progressive in how it accepted gay couples than other areas of the country.

The first time they bought a car together, López said, the employee at the dealership filling out the paperwork realized the document only had space for one name, and a spouse.

“He didn't know how to handle it. Then he goes, ‘I hate these forms.’ And he scratches it out,” López said.

The couple was together for almost 20 years by the time the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that denying same-sex couples the right to marry violated the state’s constitution.

All of a sudden, they could get married in six short months.

“We had been together almost 20 years and neither one of us expected the level of emotion that we had by actually getting married and making vows and having a clergy person bless the union."

Andrew Sherman

López was out of town for work when he received a text from Sherman that day in 2003: “SJC says yes to marriage, want to do it?”

“Fortunately, he said yes in the text,” Sherman said. But it took a minute — this was before cellphones had full keyboards, and you had to use the number pad to select letters.

The couple never wanted a civil union or commitment ceremony, which were common among other LGBTQ couples at the time but didn’t carry any legal weight.

“But once you could get married, we did go the first day. We were beyond excited,” Sherman said.

López and Sherman said they hadn’t grown up thinking about getting married — they didn’t think it was going to be a possibility in their lives. And that also meant once it became possible, there was a lot to think about, for both the couple and the institution where they wanted to get married.

“The rabbi at Temple Israel said, 'If you're going to do it, you have to have a meeting with me. We have to discuss what marriage means. We have to plan the ceremony,' ” Sherman said. “And we hadn't thought of any of those things.”

“The groom typically breaks a glass at the end of the ceremony, but what do you do with two grooms?” Sherman added. “So that was a whole discussion.”

The couple opted to each break their own glass at the same time.

“We rehearsed," he said. “It was perfect.”

Sherman said the day felt historic — despite how quickly they threw it together.

They wore suits, got boutonnieres, and Sherman’s father, who owned a jewelry store, brought a little box full of rings for them to pick from.

“It was really the most joyful day of our lives,” Sherman said.

They shared short vows: “All we said was to love, honor, and be best friends,” López said.

“We had been together almost 20 years and neither one of us expected the level of emotion that we had by actually getting married and making vows and having a clergy person bless the union,” Sherman said.

They were among many couples who had been together for a long time who got married in those first few days that it was legal.

“We all have the same anniversary. … It's really kind of exciting,” Sherman said.

“You don't forget your friends' anniversaries when you all got married within a few days of each other,” López added.

It would be another 11 years until their marriage was recognized federally. They were able to file taxes jointly in the state, but had to file separate returns for the federal government. López was able to be on Sherman’s health insurance, but they had to pay taxes on the value.

But one change stood out overall.

“When we did get married, what we should have expected, but didn't, and then observed was that people understood what that meant,” Sherman said. “People understood if you were married, that had thousands of years of history behind it and what that meant about your relationship and your relationship to your extended families and to the broader world — it just made a huge difference.”

“The act of getting married is a public act,” Sherman continued. “When you get married, there's no hiding. I think most people today don't think about hiding the way 40 years ago we thought about hiding or just not being too public.”

The couple now lives in Boston’s South End. Sherman has worked at a consulting firm for nearly 40 years, and López is a writer. They spend a lot of their time reading, walking around and talking. They like to take trips to other cities and walk there, too.

They say they don’t fight much — unless they’re hungry, then they’ve been known to get a little cranky. They pride themselves on their ability to share.

“We always order separate things when we go out to dinner and then have halves,” Sherman said.

And this year, for their 40th anniversary as a couple and 20th anniversary married, they’ve planned a full year of celebrations.

Their advice for finding a spouse?

“Marry somebody better than you deserve,” López said.

“We each married somebody better than we deserved,” Sherman replied.

Thanks to The History Project for their contributions to reporting this story.

This segment aired on May 17, 2024.